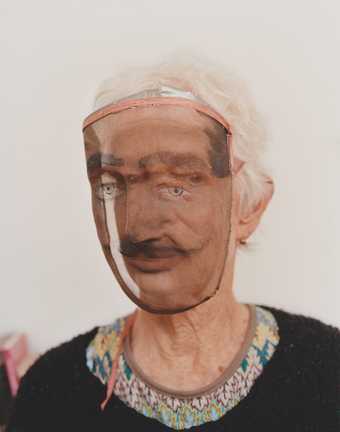

Pablo Picasso with his painting Nude, Green Leaves and Bust 1932 at rue La Boétie, Paris. Photographed by Cecil Beaton, 1933

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby's

On 25 October 1931, Pablo Picasso turned 50. Eight months later, on 16 June 1932, his first large-scale retrospective opened at the venerable Galeries Georges Petit in the heart of Paris. The display of 225 paintings, seven sculptures and six illustrated books was to cement his position as a titan of 20th-century art. When the exhibition transferred to the Kunsthaus Zürich later that year, it was to become Picasso’s first major museum exhibition. To all intents and purposes, he had made it.

Wind back 30 years, and his ascent in the art world seems all the steeper. Having arrived penniless to the French capital, like so many other international artist migrants, he had quickly been recognised as the most consistently inventive of the bunch. He had won over critics, collectors and dealers alike with his blue odes to the melancholia of the modern age and his pink depictions of circus life. Together with his friend, Georges Braque, he had created cubism, a shock as seismic to the traditions of Western painting as the Renaissance had been half a millennium earlier.

‘Few anticipated that within months the world would be thrown into turmoil again’

The trauma and instability of the First World War made the commercial and social success he enjoyed throughout the 1920s all the sweeter. Thanks to his new dealer, Paul Rosenberg, and the latter’s business partner, Georges Wildenstein, Picasso was one of the first artists to enjoy what, at the time, amounted to global representation. He lived in a grand apartment on rue La Boétie in the elegant 8th arrondissement, not far from the Champs-Élysées. He dressed in custom-tailored suits from London’s Savile Row and owned a chauffeur-driven Hispano-Suiza. When a young Jim Ede (then Assistant Keeper at Tate Gallery) expressed surprise on seeing Picasso’s limousine, the artist laconically commented: ‘I am a great master now – you have to have a motor car.’

Picasso had also become respectable in his social life. Having fallen deeply in love with the Russian ballerina, Olga Khokhlova, who was part of Sergei Diaghilev’s legendary Ballets Russes, Picasso married her in 1918. In early 1921, their young family was completed by the arrival of a son, Paulo. The Picasso household soon turned into one of the epicentres of Paris social life, with Olga and Picasso mingling with an international jet set. The press covered their attendance of cinema, theatre and opera premieres, and their holidays were spent in the newly fashionable south of France.

By 1932, however, Picasso increasingly experienced the trappings of success as a gilded cage. He missed his artist friends of old. He wanted to be closer to the discussions around contemporary art, not least the storm that was surrealism. More and more often, he escaped from family life to Boisgeloup, a manor house in the Normandy countryside, which he had bought in 1930. At the same time, he jealously guarded a relationship with the much younger Marie-Thérèse Walter, whose life-affirming physicality and utter lack of pretension would become a major influence on his work from the early 1930s.

As his June retrospective approached, Picasso knew that his critical success was not assured. He had turned down invitations from the Museum of Modern Art in New York as well as the Venice Biennale in favour of presenting his work to the world as he saw it himself: full of contradictions, resistant to being put into neat drawers of stylistic sequence, unruly and yet utterly consistent.

In the Galeries Georges Petit, pride of place was given to his works from the first half of 1932. These were lavishly colourful, sensual reworkings of the classical themes of Western art: seated figures enveloped by voluminous armchairs, still lifes and reclining nudes. Old friends, such as Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, who had been rather sceptical of Picasso’s development post-cubism, described themselves as ‘stunned’ by what they saw. Young admirers such as Alfred Barr, founding director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, applauded Picasso’s 1932 paintings as among the best work he had ever produced.

Nobody visiting the Georges Petit retrospective, least of all Picasso himself, could have guessed that following this summary of the extraordinary achievement of his life so far, he would have another 40 years of continuous reinvention ahead of him. Equally, while all the signs were there – from the ripples of the Great Depression to the rise of nationalist populism across Europe – few anticipated that within months the world would be thrown into turmoil again, leading to violence and destruction on an unprecedented scale.

On 26 February 1932, Picasso’s La Coiffure from 1905 set an auction record. One day earlier, the German government had naturalised Adolf Hitler in order for him to stand in the March and April presidential elections. Though he lost on both occasions, the wildfire that would soon engulf the world had been set irrevocably alight. If love had been the guiding star of Picasso’s life and art in the early part of 1932, and fame its crowning summer glory, by the end of 1932 the signs of tragedy were writ large. The precarious balance in both his life and the world at large, which had made 1932 Picasso’s ‘year of wonders’, was soon to reach breaking point. Once broken, the pieces would never be put together in quite the same way again.