As part of the museum-wide project Reshaping the Collectible, the research team explored how technological and institutional contexts have impacted our understanding of net art. The result is the ‘Lives of Net Art’ case study, which includes this overview of the preservation issues, articles on each of the commissioned artworks and a concluding paper by curator Sarah Cook.1 The case study arose from curators’ recognition of the cultural importance of web-based art and the identification of a lack of institutional expertise and infrastructure to support it.

The research team for Reshaping the Collectible includes colleagues with expertise in conservation, archives and records management, art history and curating. This interdisciplinary approach allowed us to identify the knowledge and infrastructure needed to preserve web-based art and build a case to develop that infrastructure at Tate. We began to develop cross-departmental collaboration with the Technology and Digital departments, extending the discussion of web-based conservation beyond the Curatorial, Legal and Collection Care teams. When the Reshaping the Collectible project began in 2018, Tate had just one artwork in its collection that included a website: Sandra Gamarra’s LiMac Museum Shop 2005, a fictional museum in Lima that ‘reproduces thrgouh [sic] the use of painting works by other artists and creates LiMAC collections and exhibitions, that mostly are shown on its constantly updated webpage’ (figs.1a and 1b).2 Tate was in the process of acquiring three more: Yinka Shonibare’s The British Library 2014 (acquired 2019; figs.2a and 2b) and Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries’ The Art of Silence and The Art of Sleep both 2006 (acquired 2021).

Fig.1a

Sandra Gamarra

LiMac Museum Shop 2005

© Sandra Gamarra Heshiki

Photo: Tate Photography

Fig.1b

Sandra Gamarra

LiMac Museum Shop 2005

© Sandra Gamarra Heshiki

Photo: Tate Photography

Fig.2a

Yinka Shonibare

Screenshot of the website for The British Library 2014, https://thebritishlibraryinstallation.com/

Fig.2b

Yinka Shonibare

Installation image of The British Library 2014

© Yinka Shonibare. Co-commissioned by HOUSE 2014 and Brighton Festival. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London.

We decided to focus our research on the commissioned artworks archived on the Intermedia Art website.3 In 2008 the Intermedia Art microsite was launched to present the archive of net art works as well as new commissions, essays, broadcast and event listings.4 Focusing on the artworks presented on these pages gave us a varied group of works with different technologies and conceptual questions to study. However, with the exception of the two recently acquired pieces by Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, these works are not in Tate’s collection. Therefore, although we could study the artworks to test tools and approaches, we could not ensure their long-term preservation. To take the phrase Graham Harwood uses in his own net art commission for the museum, there is an ‘uncomfortable proximity’ to this research: these artworks are part of the history of Tate and net art, but they do not have equal status with artworks in the collection. Tate’s website has been through several iterations and redesigns since the net art commissions, and although the Intermedia Art pages still exist, they live in a historic version of the site that is not integrated with or navigable from the current website.5 Personally, after learning so much about the artworks and the people involved, I feel very close to them, and it is uncomfortable for me to leave them as they are. I wish I could bring them all back online.

The project began in 2018, ‘just in time’ to coincide with the shutdown of Adobe Flash in 2020, a core web technology that enabled the display of animated and interactive elements on webpages. This timing allowed us to see the effects of the shutdown, but also the efforts to save Flash.

Rather than having a dispiriting effect on the project team, the loss of Flash provided us with an example of what can be done when there is a wide community of users and efforts focused on preservation. It also raised the question of Tate’s responsibility to support these community efforts. Adding a new medium such as web-based art to Tate’s institutional expertise requires close collaboration with departments not usually directly involved with preservation. In the next section we will briefly discuss those materials and how, in combination with the conceptual aspects of the works, they drive questions of preservation.

The materials and work defining properties of web-based art

Web-based art is art that uses the world wide web. This often involves a screen that displays a browser window, within which an artwork is performed, viewed and interacted with. More recently, artworks have also been made as apps, where there is no browser. Work-defining properties, or the properties that should be preserved to provide an authentic experience of a work, go beyond the technologies of production.6 For web-based art these properties might include collaboration between visitors (as in agoraXchange 2003 by Natalie Bookchin and Jacqueline Stevens), a work’s relationship to a larger offline project (as in Tate in Space 2002 by Susan Collins) or the use of information drawn from the web (as in The Dumpster 2006 by Golan Levin).7

Preserving these works requires combining technical knowledge with an understanding of their work-defining properties: What are the underlying technologies used to create a web-based artwork and how do they come into being on our screens? What are its materials? Only with this knowledge can we evaluate what will fail in the short or long-term, how it will fail and what can be done to avoid or mitigate this loss. The next section sheds some light on both these aspects.

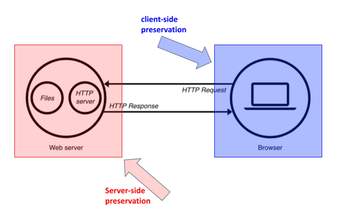

Like all online content, web-based art relies on two distinct but connected environments: first, the host or server-side environment, where the software and media are stored and made accessible to the web; and secondly the client, which provides access to the software and media in the host server, and reads and displays it. The host system requires the same type of upgrading and patching needed by any server. The client side, on the other hand, is variable and depends on the hardware and software environment used by the public to access the web. This could be a PC using Windows XP, a mobile phone, tablet, or any other device that provides internet access and has a screen.

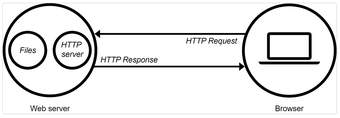

Fig.3

Diagram illustrating the communication between a web server (host) and browser (client)

Source: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Learn/Common_questions/What_is_a_web_server by Mozilla Contributors, CC-BY-SA 2.5

Any website, including these artworks, relies on an underlying infrastructure of networks, standards and protocols. These include the internet, ‘a global network of interconnected computer networks that can communicate with each other via a shared communication protocol (Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol)’8 and the World Wide Web, a ‘system of Internet servers that use HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) to transfer documents formatted in HTML (Hypertext Mark-up Language)’ to be viewed in web browsers.9

The key element here is the browser (or app) that receives the data from the host and interprets it to its own environment. They affect how web-based art is seen, and different browsers may display the same artworks in different ways.

All the artworks included in the Intermedia Art website are browser-based, rather than apps.10 They are therefore heavily dependent on the technologies involved in the production of a webpage, such as web servers. The software and web standards community Mozilla describes a web server as either software, hardware or a combination of the two (fig.3).11 The hardware element is ‘a computer that stores web server software and a website's component files... It is connected to the Internet and supports physical data interchange with other devices connected to the web’. On the software side, a web server ‘includes several parts that control how web users access hosted files, at minimum an HTTP server’. Mozilla describes this as:

An HTTP server is a piece of software that understands URLs (web addresses) and HTTP (the protocol your browser uses to view webpages). It can be accessed through the domain names (like mozilla.org) of websites it stores, and delivers their content to the end-user's device.

At the most basic level, whenever a browser needs a file which is hosted on a web server, the browser requests the file via HTTP. When the request reaches the correct web server (hardware), the HTTP server (software) accepts request, finds the requested document (if it doesn't then a 404 response is returned), and sends it back to the browser, also through HTTP.12

Many of the net art commissions make use of software beyond HTML. The most frequently used is the multimedia software platform Adobe Flash (formerly Macromedia Flash and FutureSplash; discontinued 2020), which is essential to display six of the fifteen artworks.13 Flash was a uniquely powerful technology that changed the way websites were designed, expanding the possibilities for animation, sound and interactivity.14 It was widely used from the late 1990s to the late 2010s, and appealed to artists for its ability to ‘display interactive multimedia across any browser and over almost any internet connection, requiring only the download of a small player’.15

Other technology used in the net art commissions includes Java applets, which were used in The Dumpster by Golan Levin, and which stopped being supported by browsers in 2017,16 and the software Pure Data, which Achim Wollscheid used in Nonrepetitive.17 The technologies available for creation and display, as in any other medium, deeply shape an artwork and are often marks of an artist’s training and interests. Wollscheid’s use of Pure Data, for example, reflects his background in experimental music, where Pure Data is used to create interactive computer music and multimedia works. Using it in the context of this work allowed him to create music in a continuous online collaborative process.

Technology alone is not sufficient to preserve an artwork, and care frameworks must be put in place to ensure the long-term preservation of these works. There are also conceptual reasons why an artwork may be lost, and thought must be given to what remains as documentation, testimonies or an archive. I continue to discuss these aspects in the following sections.

What does it mean to care for web-based art in an institution?

One might ask how a museum could justify buying net art, something that is freely available online and that doesn’t necessarily bring visitors through an institution’s doors. Another common concern expressed by collecting institutions is that web-based art is very fragile in terms of longevity and could disappear at the press of a button. Collecting web-based art is less a matter of ownership in the traditional sense, therefore, than a statement of ongoing care for the acquired artwork. Adopting a care-focused collection of web-based art is essential if we want to understand and document the early days of the internet and the art being made since, on and offline.

In my view, preserving web-based artworks means keeping them viewable online, for as long as possible and even if a degree of loss is involved. Achieving this in a way that maintains the artwork’s original functionality over time is often technically very challenging. In this, Tate benefits greatly from other efforts in the area, in fields such as web-archiving and software preservation, as well as specifically software-based art preservation.

Another aspect of caring for these artworks at Tate is the institutional context. While collaboration between Collection Care, the Curatorial and Legal departments is frequent and well established, the conservation team collaborates less frequently with colleagues in Digital (who are responsible for the Tate website) and Technology (who are responsible for IT infrastructure). Maintaining web-based art on the Tate website requires the expertise and collaboration of all these teams. The Technology team, for instance, highlighted the security concerns related with accessing deprecated software and the importance of maintaining up-to-date web servers. The Digital team provided an understanding of these artworks in the wider context of the Tate website. They focused on user experience: how those visiting the site find and connect with the net art commissions; how a webpage can be clearly identified as an artwork; and how the institution manages an artwork page that does not follow current best practice, for instance in terms of accessibility.

For any artwork created using reproducible media – from video and film to paper prints remade from a PDF for each exhibition – Tate strives to have the means to preserve each artwork over time, and in close collaboration with the artist. For instance, to be able to continuously update and preserve The British Library 2014 by Yinka Shonibare, Tate worked with the artist's studio to transfer the website to a Tate server. Such a transfer presents both benefits and potential disadvantages for the artist. It means the museum will be able to support the artwork’s digital infrastructure beyond the life of the artist, but also that the artist loses a degree of control, including the ability to change and update the site (even where this is enabled, it can be more time-consuming). This sort of transfer therefore requires the artist or their representatives to trust in the institution's capacity to care for the work in the long term.

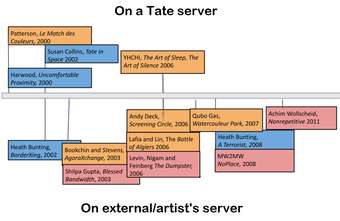

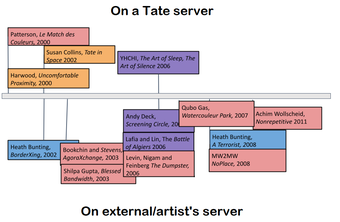

Fig.4

Timeline of the artworks commissioned for Tate’s websites between 2000 and 2011. Above the midline are works hosted on a Tate server, and those below are hosted externally, most often on the artist’s server. Their colours indicate their condition in 2018, before Flash was discontinued. Blue means online and low risk albeit possibly with some loss; orange means online and at high risk of loss; and red means offline.

The timeline above (fig.4) shows when specific artworks were commissioned and whether they were stored in Tate servers or the artists’ own. The colours indicate their status in 2018 (at the beginning of the current project): whether they are online and low risk albeit possibly with some loss (in blue), online and at high risk of loss (in orange) or offline (in red). Only four works are hosted on the Tate server, probably because during these initial commissions, artists worked closely with the Tate web team and Tom Betts, the first web editor at Tate (1997–2001).18 The other artworks were hosted externally on servers managed by the artists.

We began this process with the assumption that artworks would be safer on Tate’s server than on artist’s servers. However, we found that artworks hosted on artist’s servers were in some cases perfectly maintained and updated, and still running as designed. Such examples include Andy Deck’s Screening Circle and Heath Bunting’s two works, which can be accessed in full.19 At the other end of the spectrum, some artworks on artists’ servers were completely offline. In some cases, such as with Nonrepetitive by Achim Wollscheid, this is because Tate’s contract with the artist stipulated the period the work would be online, and only covered the hosting costs for that period. Artists mentioned that the cost and effort of maintaining the artwork online over time could be a burden, especially if the work is no longer regularly accessed.20 As can be seen in the diagram, in 2018 all three works on a Tate server were still online.

However, the artworks had not been maintained over time, resulting in broken links, unreadable images and issues with changes to HTML standards, namely in Le Match des Couleurs 2000 by Simon Patterson.21 Despite these losses, because the works are on Tate’s servers, we still have access to the software environment and digital assets needed to make them accessible again. This is described as server-side preservation and will be discussed in the ‘Preservation strategies’ section below. The main challenge around care here is not directly one of technological possibility, but the fact that because these works are not in the Tate collection, there is no dedicated resource for maintenance or intervention.

Fig.5

Reconstruction of the timeline shown in fig.4, here updated to show the status of artworks in 2023, after Flash was discontinued. The purple in the diagram shows works that had undergone preservation interventions during the period of the current case study.

Reconstructing the diagram for 2023 (fig.5) illustrates a major shift around the discontinuation of Flash in early 2020. Because the infrastructure to support these works was not in place, and maintaining them online had not been defined as a priority, the artworks hosted on Tate servers went offline at that time. Artworks that are still online were either technologically simple (the works by Bunting, Harwood, Collins), were maintained by the artist’s themselves (Deck) or in collaboration with a museum as part of their collection (Marc Lafia and Fang-Yu Lin, Heavy Industries).

Preservation strategies

Fig.6

Diagram illustrating the focus of the two main modes of preservation: server-side (in red) and browser-side (in blue)

Image courtesy Mozilla and the author

This section will give an overview of the most common approaches to the preservation of online content and then introduce the specificities of preserving web-based art. In an art context there are two main approaches for preservation: client-side and server-side preservation (fig.6). Client-side preservation uses software tools derived from web-browsers to record the information that a browser receives. As a visitor comes to a webpage, the files needed to view the page are downloaded to the browser. By capturing these it is possible to create a copy of the page.

The recording software for captures at scale is called a crawler, and it can be used on freely accessible websites on the Web.Heritrix and Wget are two common crawlers, the first developed by the Internet Archive, the second by the GNU project.22 Crawlers are used by web archives, such as the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, the UK Web Archive at the British Library and the UK Government Web Archive at the National Archives.23

This approach allows the automated capture of large numbers of websites, to cover for instance all the websites under a specific country domain but has some limitations. As described in the guidance for website managers by the National Archives, these limitations include the inability to capture ‘Flash animations and games, streaming media and embedded social media’.24 New tools, however, are constantly being developed to address these limitations. The Internet Archive, for example, has now incorporated the Flash emulator Ruffle into its platform so that it can playback some Flash files. This has been driven by the wide application of Flash content in the web, especially in online games, the makers of which are working to support preservation efforts.25

Other tools are being developed to support small-scale web archiving. In collaboration with Rhizome.org, software engineer Ilya Kreymer developed Webrecorder (later Conifer), a tool aimed at small-scale client-side preservation. It requires little technical knowledge to use, making it possible for institutions to create focused collections of web content. In 2020 Reshaping the Collectible Archives and Records Researcher Sarah Haylett used Rhizome’s Conifer platform to capture the Intermedia Art microsite and the artworks held there.26 Since the project began, Conifer/Webrecorder has continued to develop tools, including added emulated browsers, so that a page can be seen in a browser of the period the page was created.27 Webrecorder and most crawlers store data in the form of WARC (WebARChive) files, an archival format that ‘combines multiple digital resources into an aggregate archival file together with related information’.28

Sarah Haylett and the Time-based Media Conservation team have been collaborating in creating Webrecorder captures of the current website. These capture media and Flash elements that most web archives could not, so the recordings are more complete than those historically captured by the UK Government Web Archive (UKGWA). The Webrecorder WARC files can be played back locally in the Tate Library and Archive or online on the Conifer platform and on replay.webpage, another tool developed by the Webrecorder Project. We also submitted copies of the files to UKGWA so the Flash elements in the pages can be made accessible once the archive is able to support playback.29

Server-side archiving requires creating copies of the web server, with all its component parts, so that it can be rebuilt for access via the web. Depending on the original environment and type of access, this could mean creating a disk image of the server where the pages are hosted or creating copies of the data in the server and rebuilding the site. Server-side archiving opens a series of possibilities for long-term preservation, namely in relation to emulation, but it is only possible if the conservators or archivists have access to the server. If one holds a disk image, or the data needed to create one, then that data can be run in either a virtual machine or emulator, set up with a security layer to mitigate risks to the wider institutional web infrastructure.30

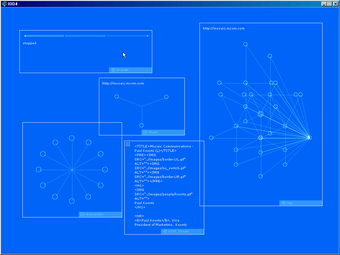

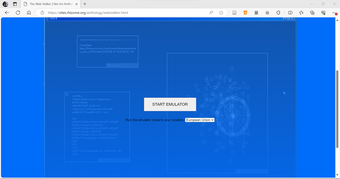

The Webrecorder Project’s browser emulator oldweb.today provides access to historical browsers so a website can be seen in a browser of its own time. It also supports the playback of Flash files and Java applets. In 2018, Tate worked with researchers at the University of Freiburg to test the results of accessing a webpage via an emulated browser. At that time, the main limitations of this approach were around speed, so user interactions had a slight but noticeable delay, and audio was often out of sync with images. Since then, however, the tools have improved and the emulated results are largely indistinguishable from the original works.

Fig.7a

The interface of The Web Stalker 1997 by I/O/D

Source: https://rhizome.org/editorial/2017/may/30/preservation-by-accident-is-not-a-plan/

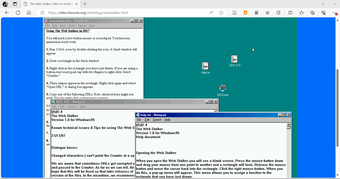

Fig.7b

The browser window with the user interface to start the emulator. Note that the dimensions of the emulator window are constrained within the browser window to maintain the original aspect ratio of a screen in 1997.

Fig.7c

Windows 98 starting in the emulator

Fig.7d

Instructions to use The Web Stalker within the Windows 98 emulated environment

Fig.7e

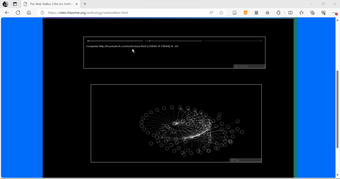

The Web Stalker interface displaying results of a crawl

Emulation is being actively researched in the digital preservation community as a way of accessing data in its original format.31 A successful example is the use of emulation by Dragan Espenschied, Preservation Director at Rhizome, to enable local access to The Web Stalker 1997 by artist collective I/O/D in 2016 (figs.7a–e).32 This software project is an alternative browser developed to read, manipulate and present web data in radically different way to the other browsers of the time. It runs on Windows 98 and as part of Rhizome’s Net Art Anthology visitors can use the browser on this operating system, made possible by the use of the emulated environment.33

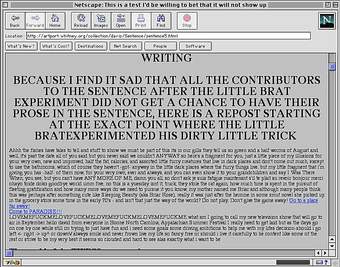

Fig.8a

Screenshot of The World’s First Collaborative Sentence 1994 by Douglas Davis. Captured in 1994 on an early version of the Netscape browser.

Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Fig.8b

Screenshot of The World’s First Collaborative Sentence 1994, remade (live version) 2012, by Douglas Davis. Captured in 2023 in Google Chrome.

Source: https://artport.whitney.org/collection/DouglasDavis/live/Sentence/sentence5.html

While web archiving and emulation are key to the preservation of web-based art, it often is necessary to intervene on the code of the page to preserve the experience of an artwork. Examples of this approach include work undertaken by New York University students at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, under the supervision of Professor Deena Engel and Conservator Joanna Phillips. The students painstakingly restored two works – Brandon by Shu Lea Chang and Unfolding Object by John F. Simon Jr – at the level of the code.34 They documented every intervention so that anyone looking at a webpage with developer tools can see the new or edited lines among the original code. Another interesting example of restoration through code is that undertaken in 2012 by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, of Douglas Davis’s The World’s First Collaborative Sentence 1994, a net art work in which users were invited to contribute to a never-ending sentence (figs.8a and b).35 The conservation team opted to maintain access to two versions of the work, one maintaining the original code but losing the ability to input into the sentence, the other altered to allow interaction.36

For some web-based artworks, the only conservation option available may be documentation. This includes screenshots of web pages, screen recordings of a website being navigated or video recordings of users navigating websites. Screenshots are often made by the artists themselves or by teachers and researchers that study or teach an artwork. One example of the documentary value of screen recording is the video created by Golan Levin for The Dumpster, where the artist explains the functionality of the work as he interacts with it.37 When we began researching The Dumpster browsers no longer supported Java applets, and these were also not viewable in the Wayback Machine recordings. The video was therefore the only way we could see how the work looked and functioned.38

Beyond technology

The preservation of web-based art is not only dependent on technologies of production but must also consider questions around an artwork's concept and aesthetic. These concerns are often interrelated. One important aspect of conservation is understanding how artworks relate to their context. In the case of the net art commissions, the immediate context is the web, and specifically Tate’s institutional website. Two of these works, Susan Collins’s Tate in Space and Graham Harwood’s Uncomfortable Proximity, function as institutional critiques of Tate by aping or mimicking the museum’s own website. The way that the works appears to a visitor, and its alignment with the institutional website, is therefore central to its meaning.

Fig.9

Tate in Space on the Tate website in 2023 next to the homepage of the Tate website in 2003. Capture taken by the Internet Archive on 3 June 2003. Note the link on the homepage reflecting the Tate in Space pages.

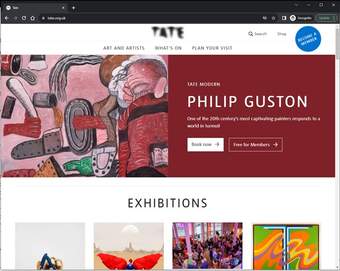

Fig.10

Homepage of the Tate website

Screenshot taken 12 October 2023

Tate in Space builds a digital presence on the museum’s website for a new, extraterrestrial Tate gallery (fig.9).39 In addition to the Tate’s locations in London, Liverpool and St Ives, there was to be an expansion into space, with the new museum housed in a satellite designed through an open competition. The web pages that comprise the artwork present the activities related to the development of the new site. The Tate in Space pages were designed to be indistinguishable from those dedicated to Tate’s other locations, using the same page formats and design. The current website has a very different aesthetic and layout (fig.10), so the Tate in Space pages are clearly marked as separate and anachronistic to the institutional site. Furthermore, in 2003, the link to ‘Tate in Space’ appeared below St Ives on the homepage’s menu bar (see fig.9), adding to the ruse and giving the artwork a central position on the website. Now the work can only be accessed via a direct link or through an external search engine, as a search in the Tate website returns no results.

The works by Heath Bunting, BorderXing Guide and A Map of Terrorism (part of The Status Project), on the other hand, are hosted by the artist, and keeping them as part of the artist’s website provides context to artist practice and although it would be possible to ‘remove’ them, that would constitute a loss. This is particularly the case for A Map of Terrorism, where the PDF diagram map is one of the many outputs of a database kept by Bunting.

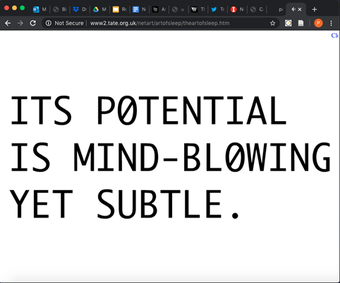

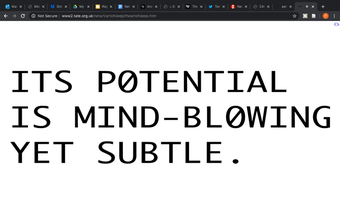

Another type of anachronism relates to how web pages look on physical devices, and the work The Art of Sleep by Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries is an excellent example. When the original Flash version was created, in 2006, it would have been seen on the screen of a personal computer, and at the time the default aspect ratio for computer monitors was 4:3. In 2023, most computer monitors will have an aspect ratio of 16:9 and so the original Flash would have appeared stretched out. Because the artists are so interested in the typography and graphic design of their work, this is a big difference. Because the work was transferred to video in 2018, upon its acquisition by Tate, the version now available online does not present this behaviour, but does have much wider white margins.

Fig.11

The Art of Sleep 2006 by Young-hae Chang Heavy Industries, displayed with a 4:3 aspect ratio

Fig.12

The Art of Sleep 2006 by Young-hae Chang Heavy Industries, displayed with a 16:9 aspect ratio

Fig.13

The 2018 version of The Art of Sleep, showing wider white bars on each side of the text

This means, for instance, that a page that used to look like fig.11 would now appear as fig.12. The new version of the work appears as fig.13.

A different set of questions arises for websites with participatory elements that welcome contributions from the public. Tate in Space includes such elements through its architectural competition, and participation is central to agoraXchange by Natalie Bookchin and Jacqueline Stevens.40 Both of these works included forums that were active for several years following the launch of the sites. When the activity in the forums wound down an essential part of each work was lost. After the chats were closed to new contributions, the early discussions became documents or a record of each artwork.

Screening Circle by Andy Deck highlighted another key contextual issue in the changing way users interact with the web.41 During the Lives of Net Art event at Tate Exchange, the work was shown on a PC, using mouse and keyboard, but what conservator Chris King found was that younger people were struggling to understand how to interact with the interface; visitors were not sure what to do.42

The net art works explored in this case study have at times appeared like time capsules, as artworks kept in limbo, online but difficult to find, with bigger or smaller losses to their functionality, concept and relational context. There are exceptions to this. Screening Circle, for instance, has been carefully maintained by the Deck to remain functional, while Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries worked closely with Tate to preserve and transfer The Art of Sleep and The Art of Silence to museum servers. Fang-Yu Lin made a new installation version of his and Marc Lafia’s work The Battle of Algiers for display in the exhibition Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018 at the Whitney.43 He also created an emulated version of the work, and hosts both versions on his website.44

The way an artist chooses to engage with the preservation or redisplay of an artwork, especially when the context changes from screen to gallery is highly individual. While Fang-Yu Lin facilitated the public display of The Battle of Algiers by revisiting the work, Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries did not want their web-based art to be shown in the gallery. For Tate’s Media Networks display at Tate Modern, their works were presented via QR codes on the gallery wall so that people could see the works on their personal devices. This difference in approach is related not only to the artist’s preferences, but also to the technical requirements of the artworks and curatorial decisions.

Conclusion

The appetite for collecting web-based art can be hampered by a general perception of websites as ephemeral, fragile and prone to disappearing overnight. This is visible to internet users through the occurrence of 404 error pages, missing content and ‘link rot’, a term to describe links that no longer lead to the intended destination.45 But through this project – and witnessing the concurrent ‘failed demise’ of Flash – we have learned that web-based art can be very resilient.

Unlike other software-based art, which can rely on dozens of different programming languages and hundreds of different types of software, web-based art from the 1990s and 2000s (notwithstanding the emergence of social media) relies on only a handful of technologies, mostly with open standards. Further to this, there is an active community of users working to maintain these technologies, one which extends beyond artists and includes anyone that hosts information on the web. This means that people with many different skills and interests can come together to identify problems and find solutions for preservation.

The end of support for Flash in 2020 provides a powerful example of community preservation efforts. it is impressive to see how software developers and preservationists came together to find solutions to keep work online. Although these efforts are largely targeted at games, many could feasibly be applied to web-based art.46 The ability to share preservation strategies with other fields makes the technological aspects of preservation surmountable. We found that the real challenge will be to build a new model of collaboration for and between different teams at Tate. This can only be achieved if there is a clear priority established by the institution and if web-based art is valued in the same terms as work in other media. Bringing web-based art into the collection is the most important step, so that resources can be made available for full preservation interventions, and so that the infrastructure and knowledge that already exists in the institution can be extended to support this part of art history.