Liubov Popova’s engagement with design in general and textile design in particular should not be seen as the result of a sudden decision, made as an impulsive response to a call for artists from the First State Textile Printing Factory in 1923.1 On the contrary, it should be seen as the culmination of extensive thought and activity, including the artist’s decision to adopt the constructivists’ position in 1921, and her subsequent determination to use her artistic skills, not to create works of art as such, but to participate in the construction of the new Communist environment by using those skills to design new everyday objects for mass production.2 In this essay I shall look at the circumstances surrounding Popova’s involvement with constructivism and her approach to fabric design. I shall also explore the ways in which her designs reflected and, indeed, sometimes continued the concerns that had been fundamental to her activity as a painter.

Popova did not join the Working Group of Constructivists when it was set up in Moscow in March 1921, but by the end of the year, her statements make it clear that she had embraced the constructivist ethos. Towards the end of 1921 she wrote: ‘Our new aim is the organisation of the material environment, i.e. of contemporary industrial production, and all active artistic creativity must be directed towards this.’ 3 She elaborated these ideas further in a text dated 21 December 1921:

The era that humanity has entered is an era of industrial development and therefore the organisation of artistic elements must be applied to the design of the material elements of everyday life, i.e. to industry or to so-called production.

The new industrial production, in which artistic creativity must participate, will differ radically from the traditional aesthetic approach to the object, in that primarily attention will be focused not on the artistic decoration of the object (applied art), but on the artistic organisation of the object in accordance with the principles of creating the most utilitarian object …

If any of the different types of fine art (i.e., easel painting, drawing, engraving, sculpture, etc.) can still retain some purpose, they will do so only

1. while they remain as the laboratory phase in our search for essential new forms

2. insofar as they serve as supportive projects and schemes for constructions and utilitarian and industrially manufactured objects that have yet to be realised.4

These ideas are essentially identical to those expressed in the programme of the Working Group of Constructivists, which had been written by the theorist Aleksei Gan and to which the artists of the group such as Aleksandr Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova, agreed. What Popova omitted from her text is the word constructivism. Apart from that, her final paragraph makes it clear that, like the constructivists, she was eager to use her artistic skills in the design of useful objects for mass production.

This did not represent a sudden change of heart on Popova’s part. Although she had not joined the Working Group of Constructivists, she had exhibited with Rodchenko and Stepanova in September 1921 at the 5 x 5 = 25 exhibition.5 In this show she exhibited paintings that she called ‘spatial force constructions’ and wrote in the catalogue that the paintings exhibited ‘are to be regarded only as series of preparatory experiments towards concrete material constructions.’6 Moreover, in spring 1921, she had worked with the architect Aleksandr Vesnin and the avant-garde theatrical director Vsevolod Meierkhold on the sets for a ‘theatrical military parade’, which was called ‘The End of Capital’ and was to take place in Moscow that summer to celebrate the meeting of the Congress of the Third Communist International. It was conceived as a mass theatrical event, employing a cast of thousands, but it was unfortunately cancelled.7 Nevertheless, it had given her valuable experience of working in three dimensions.

At the time of her statement in December 1921, Popova was working with Meierkhold in his theatrical studio. Subsequently, she designed the set and costumes for his production of The Magnanimous Cuckold, which opened in April 1922. Here she produced a constructivist set in which the mill of the drama was transformed into an acting machine and the costumes into working overalls. The following year she produced the designs for The Earth in Turmoil. Throughout this period, Popova was teaching the discipline of colour on the Basic Course at the Moscow Vkhutemas (Higher Artistic and Technical Workshops – Vysshie khudozhestvenno-tekhnicheskie masterskie).8 This provided students with a vital artistic foundation for working on designs for industry and evolving prototypes for future mass production. In 1922 Popova argued that there should be a production workshop at the school, specifically devoted to creating concrete links with industry.9 Unfortunately, this was extremely difficult to achieve, not least because Soviet factories were in disarray and mass production was at an extremely low ebb. As Lef (Left Front of the Arts) observed, ‘Unfortunately, our industry is still far from being ready to welcome the input of our creative power. For the time being young artist-producers must try their strength wherever they can.’10

The textile industry offered one such rare opportunity. It had been ‘one of the most developed and important industries of pre-revolutionary Russia’; in 1913 there had been 873 factories, employing over half a million workers. 11 During the Civil War (1918–20), productivity had been severely reduced (almost reaching zero in 1919), and this had caused an acute shortage of cloth.12 By 1923 the industry was beginning to recover, but the disruption of links with Paris, the source of most patterns in the pre-revolutionary era, meant that artists were vitally needed.13 In June 1923, Aleksandr Arkhangelskii, who had just become the director of the First State Textile Printing Works in Moscow (formerly the factory of Emile Zindel) published, along with Professor Petr Viktorov of the Vkhutemas, an open letter in Pravda inviting artists to work in his factory.14

Such an invitation was particularly opportune for the constructivists, and may not have been entirely unexpected. Earlier, in March 1923, the critic and theoretician Boris Arvatov had given a paper at the Moscow Inkhuk (Institute of Artistic Culture – Institut khudozhestvennoi kul’tury) discussing conditions in the textile industry. He had stressed the desperate need for good designs in revitalising this aspect of textile manufacture and had gone so far as to suggest that artists should be actively encouraged to participate in the work of the factories. 15 This may have paved the way for Popova and Stepanova’s decision to accept the invitation of the First Textile Printing Works, but ultimately the invite represented an all-too-rare, concrete opportunity to become involved with a genuine industrial enterprise and real mass production.

Yet the two women were clearly aware of the problems that would be encountered in an industry where the role of the artist was firmly established and the nature of the task was essentially one of embellishment and decoration, amounting effectively to applied art. In order to counteract this pitfall and to clarify their own position, the two women submitted a memo to the factory management, which expressed their desire to be involved in all the organisational and technical aspects of the entire manufacturing and marketing processes. They said they wanted:

1. to participate in the work of the production organs, to work closely with or to direct the artistic side of things, with the right to vote on production plans and models, design acquisitions, and recruiting colleagues for artistic work.

2. to participate in the chemistry laboratory as observers of the colouration process …

3. to produce designs for block-printed fabrics, at our request or suggestion.

4. to establish contact with the sewing workshops, fashion houses, and journals.

5. to undertake agitational work for the factory through the press and magazine advertisements. At the same time we may also contribute designs for store windows.16

There is no evidence whatsoever that these requests were treated at all seriously by the factory management.

Although the precise date that Popova and Stepanova started working at the factory is not known, it was probably in the autumn of 1923.17 The idea that the artists had become involved with the printing works before this may have been based on the large number of designs that Popova produced. She was incredibly prolific. A contemporary cartoon by Stepanova illustrates this impressive productivity by showing Popova taking a whole wheelbarrow full of designs to the factory, while Stepanova modestly takes a few in her handbag.18

Despite this, all was not well. In January 1924, Stepanova reported to Inkhuk about work at the factory, criticising various aspects of the current structure of the textile industry:

1. the isolation of the drawing department from the production and marketing organs of the factory.

2. the work of the artistic atelier is divorced from the production [process].

3. the dominance of consumer taste [and] fashion.19

Apart from stressing the need to eradicate traditional approaches to textile design and the desire to promote ‘geometricised form’,20 Stepanova also outlined a precise constructivist strategy for reforming the current shortcomings of the industry:

1. to fight against handicraft in the work of the artist. To strive towards organically fusing the artist with [actual] production. To eliminate the old attitude towards the consumer.

2. to establish links with fashion journals, with fashion houses and tailors.

3. to raise consumer taste. To bring the consumer into the active fight for rational cloth and clothing.21

The tasks confronting them therefore were:

the eradication of the firmly embedded ideal regarding the high artistic value of the hand drawn design as the imitation … of painting;

the fight against naturalistic design in favour of the geometricisation of form, and propagandising the industrial tasks of the constructivists.22

This was, of course, a tall order and required, on an organisational level, a substantial commitment and an enormous amount of co-operation from the factory, which was not forthcoming.

The two constructivists were far more successful in ‘geometricising form’ and in this way propagandising the new aesthetic.23 Of course, for Popova, this new aesthetic had been primarily articulated in painting although her theatrical experiments, such as her work on The Magnanimous Cuckold in 1922, had extended her explorations into three dimensions. In designing textiles, she was back to working in two dimensions and on a much smaller scale. Earlier, in 1917, she had acquired some experience of working at this scale with cloth and texture when she had made embroidery designs for a group of peasant embroiderers in the Ukrainian village of Verbovka.24 Those designs are related to her then current artistic concerns and tend to be collage compositions, consisting of overlapping geometric elements. In 1923, she clearly had to rethink this approach somewhat when designing textiles for mass production, not least because the design had to be capable of being repeated ad infinitum in order to produce a bale of cloth, but also in the intervening five years, her own vocabulary of abstraction and her experiments with non-objective form had developed enormously.

Fig.1

Liubov Popova

Space Force Construction 1920–1

Oil with wood dust on plywood

1123 x 1120–50 mm

State Museum of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki, George Costakis Collection

Fig.2

Liubov Popova

Textile Design c.1924

Pencil and ink on paper

234 x 191 mm

Private collection

Not surprisingly, perhaps, Popova’s abstract paintings and her textile designs share several features in common, to the extent that one can truly consider the paintings as representing the ‘laboratory phase’ to which she referred in her statement of 21 December 1921. Indeed, the fabric designs tend to reveal the same kind of aesthetic concerns that motivated the paintings (figs.1, 2). Both media demonstrate Popova’s interests in exploring the potential of geometric form, exploiting the possibilities of a limited range of colours, investigating permutations of a specific form or combination of forms, working in series, examining the line and its optical possibilities, using repetition of forms to create rhythm and dynamism, extending the visual potential of the ground, experimenting with the grid as an artistic configuration, and looking at ways of creating sensations of dynamism by intersecting or dislocating forms.

Simple geometric forms provide the basic language of Popova’s paintings and textile designs. In the paintings, such forms ultimately derived from the planar organisation of cubism or the vocabulary of suprematism. While this pictorial experimentation undoubtedly provided the aesthetic basis for the use of geometric form in the fabric designs, the use of such forms also acquired additional significance from the ideological thinking of the period. Geometry was associated with the machine, and the machine, in turn, reflected the essential character of the industrialised working class, the new masters of the Soviet state. Geometric form also eradicated the sense of individual touch and associations with individual intuition and emotion in favour of a more mechanised and impersonal sense of shape and a more industrial sensibility. It could, therefore, be seen to express a more collective ethos. The exigencies of mass production and the need for a repeat in the printing process also encouraged Popova to use a far more regular and more defined geometry in the designs than in the paintings – usually the circle, the triangle and the rectangle, either alone or in combination (figs.3–6). Yet whether in the paintings or in the designs, Popova approached geometric form through its relationship to the picture plane (or ground in the textiles) and through the dynamism and contrast that is set up by the interrelationships between similar or dissimilar forms.

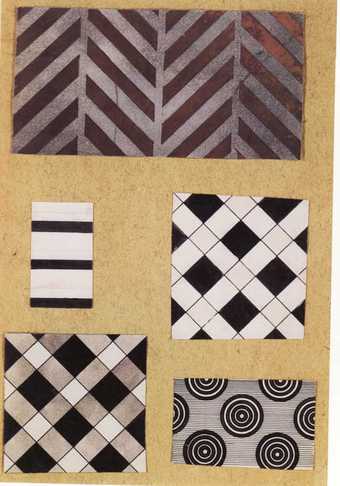

Fig.3

Liubov Popova

Fabric Designs

Watercolour on paper, mounted on paper

355 x 379 mm

Collection of T. & E. Tatsinian

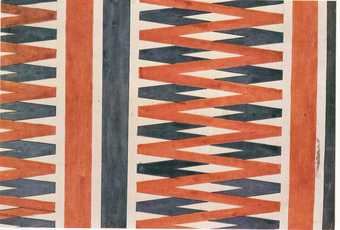

Fig.4

Liubov Popova

Textile Design 1923–4

Reproduced in Lef, no.2, 1924

Fig.5

Liubov Popova

Sample of Printed Fabric

State Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow

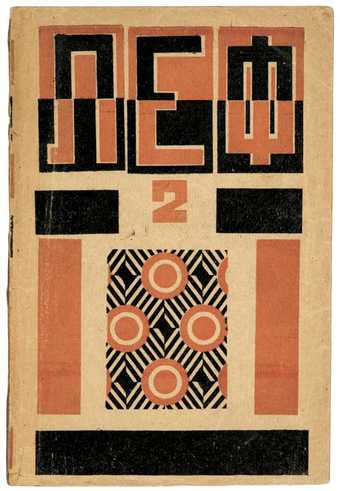

Fig.6

Liubov Popova

Textile Design 1923–4

Ink and gouache on paper

Reproduced on the cover of Lef, no.2, 1924

Both the paintings and textiles also tended to be based on exploring limited colour ranges. This is generally far more evident in the textiles than in the paintings, but it is particularly apparent in her non-figurative paintings of 1920–1, where Popova tended to employ no more than three colours, using this restricted palette to explore other pictorial concerns such as texture, or dynamism through intersecting forms (figs.1,7). Her textile designs are frequently bichromatic. Indeed, she often used only one colour in conjunction with black and white – white usually being the colour of the unprinted fabric. This approach demonstrated an interest in the relationships between printed and non-printed surfaces in the resulting swathe of cloth. At the same time, by limiting the number of colours used in the designs, Popova also conformed to the constructivists’ concern with economy, not only as an aesthetic concept but also as an industrial and financial criterion, simplifying the printing process and therefore reducing production costs.

Fig.7

Liubov Popova

Painterly Architectonic 1918

Oil on canvas

1050 x 800 mm

Slobodskoe Regional Historical Museum and Exhibition Centre

Both the paintings and textiles reveal Popova’s commitment to analysing the nature of form and doing this intensively through exploring permutations of a single idea and pursuing such explorations in a series of works, whether canvases, gouaches, drawings or fabric designs. Ever since she had started experimenting with cubism in 1914–15, Popova had worked in series, analysing her approach and producing variations of a single image.25 She emphasised that she was exploring ‘the organisation of elements … as self-contained structures’ and investigating ‘the significance of each element – line, plane, volume, colour.’26

Fig.8

Liubov Popova

Space Force Construction 1921

Oil, with wood dust on plywood

710 x 639 mm

State Museum of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki, The George Costakis Collection

Fig.9

Liubov Popova

Sample of Printed Fabric

State Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow

When Popova started experimenting with non-objective, abstract or objectless painting in 1916, her exploration of specific pictorial elements became even more intensive. Her first experiments with the new idiom resembled abstract collages with shapes in different colours layered against each other.27 Subsequently, the compositions in her paintings became far more dynamic, based on interpenetrating planes, with shading and highlighting used to intensify sensations of movement.28 By 1921 she was producing works in which the line and plane were treated autonomously as distinct artistic and plastic elements (fig.8). This rigorous investigation of a single pictorial component is particularly evident in the series of space-force compositions, which she painted in 1921. In some of these, the lines, in different colours, zigzag irregularly across the picture plane, setting up rhythms and destroying the stasis of the ground.

It is precisely this rigour of exploration of a specific form or combination of forms that can be found in the fabric designs. Although the fundamental components of each design were simple (circles, squares, quadrilaterals, or sections of these), the resulting patterns were often very complex, built up of repetitions, developments, and permutations of the simplest and most easily reproducible shapes. This practice is typical of many of the designs. For instance, one of her most complex designs (fig.2) was based on repeating at different scales and at different thicknesses circular and straight lines. At the same time, Popova created a series of designs based upon permutations of a single motif such as circles, or quadrilaterals (figs.3, 9).

Both the paintings and the textile designs demonstrate a strong engagement with the nature of the line. In certain of Popova’s paintings from 1921, there is a strong structural emphasis on the line, and this use of the line as a primary organisational element is also evident in the fabric designs (figs.8, 5, 9). In some designs, different thicknesses of lines have been used to orchestrate the surface and convey a sense of rhythm and energy (fig.2). In this instance, a series of thin horizontal lines is broken by the introduction of a thick line, which dislocates the linear rhythm and alters the viewer’s visual perception of the pattern. In other designs, regular lines of different colour produce a simple stripe effect.29

In Popova’s paintings, the lines often form a kind of irregular grid pattern (fig.8). To some extent, this corresponds to the argument put forward by the art historian Rosalind Krauss that the grid epitomised the self-reflexivity in modernist painting, emphasising the weave of the canvas and the break with naturalism.30 In Popova’s paintings, the underlying emotional charge and dynamic sensation derive from the irregularities and breaks that are introduced into the grid. In the textiles, this grid is regularised and conforms much more to Krauss’s model, although sometimes turned throuh forty-five degrees (fig.3). Nevertheless, both the paintings and the textile designs possess sensations of layering and lattice work, which suggest conflicting forces at work and often introduce tension and convey qualities of motion.

Of course, in the fabrics, the grid reflects the structure of the cloth produced by the warp and weft of the weaving process, so that the printed grid pattern actually gives graphic presence to the internal structure of the fabric. Yet within this general format, Popova produced a large number of variations. There are quite simple open grids, comprising a single grid, printed in a single colour. She produced more dynamic configurations by introducing another colour and superimposing one grid over another. In one pattern, for instance, a complex dynamic sensation is produced by superimposing identical grids, but of slightly different sizes, in different colours and at different angles, so that a blue grid is printed over a red grid, with the blue grid printed at an angle of forty-five degrees to the warp and weft of the fabric. In this instance, the grids are closely related to each other. The space between the lines forming the red grid is identical to that between the lines of the blue grid, but the inner line of the blue grid begins at an identical space from the outer line of the red grid. This introduces an element of mathematical precision into the design and into the repeat.31 While the red grid echoes the web and weft of the woven fabric, the blue grid destroys this reference and adds dynamism to the whole as well as giving a sense of depth to the design. Of course, the grid pattern also has strong affinities with traditional checked fabrics, which also exploited the weaving process to introduce pattern and variety. Popova frequently produced small designs like this for shirts and blouses, while the more flamboyant patterns were clearly destined for larger items of clothing such as dresses.

In both her paintings and the textile prints, Popova demonstrated a great concern for the ground, emphasising its role, investigating its connection with the painted or printed design, and exploring its potential to become an active component in the overall artistic structure. In the paintings on wood (figs.1, 8), the plywood was often not sized, but left as a natural colour, so that it acted less as a passive background to the composition and more of a positive textured element in the pictorial construction. In the fabric designs, too, the ground is left unprinted, remaining the colour of the cloth, usually white, and as such, it often plays an active organisational role, serving as one of the positive colour components of the configuration. Often there is only one or, at the most, two other colours used in the printing process with the white ground. For instance, in this example (fig.6) the actual ground is white, but the resulting white circle against the red looks as if it has been printed onto the fabric, rather than the other way round. This adds a sense of optical ambiguity as well as optical dynamism into the design, as the circles seem to vibrate slightly, almost like an op-art composition. Such effects were clearly intentional.

In some paintings and designs, Popova introduced a shift in the pattern, a sdvig – a shift or dislocation (figs.1, 2). For many avant-garde writers and painters, this type of disruption was a crucial element of modernist painting, representing objective deformation, which was essential to the emergence of abstract or objectless creation.32 This device is sometimes difficult to isolate and identify in Popova’s paintings, although it underlies the structure of some of the paintings on plywood (fig.1), where the continuity of different elements or configurations have been subject to a dramatic break or shift. Dislocation or sdvig is also used as a dominant organisational device in certain of the textile designs. In this particular design (fig.2) the sdvig or break in the pattern is crucial to creating visual vitality and dynamism, by disrupting the predictability and flow of the design, and adding a crucial and extra asymmetrical quality into it. The two separate halves of the circles are not identical, neither is the rhythm of the lines.

As this design demonstrates, the sdvig was merely one way in which Popova introduced dynamism into her paintings and designs. Asymmetry, irregularity, diagonal arrangements and repetitions were also used to perform this role. In this same design (fig.2), an asymmetrical composition comprising yellow, pink and black circles (of varying thickness) is set against a pattern of vertical black lines of various widths. The contrasting rhythms of these repeated circular and linear elements and the drama of the interplay between them are intensified, and the whole is endowed with an even greater sensation of movement by the diagonal break in the pattern.

In the paintings, Popova frequently used white to intensify spatial ambiguity, whether it is in connection with a planar composition or a more linear one. She also used white to stress the intersection of forms, indicate volume or to suggest dynamism. This practice of using white also translated into the fabrics. These qualities have already been discussed in relation to the diamond and circle pattern, where the white circles appear to be printed against the blue and these circles in turn appear to be printed on a black and white diamond fabric. In other instances, too (figs.9, 3), Popova has utilised optics and optical sensations to create a vibrant design that appears to be constantly shifting. In the bottom-left and middle right-hand drawings (fig.3), the white describes a positive form, so that the design sometimes seems to appear to be a white figure printed on black, and at others a black figure on white.

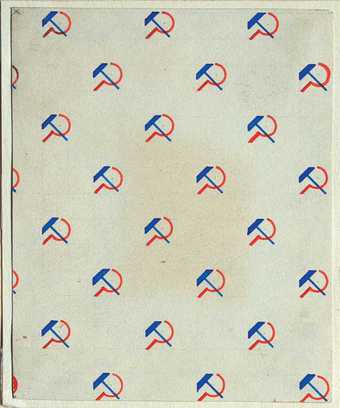

Fig.10

Liubov Popova

Textile Design 1923–4

Gouache on paper

115 x 92 mm

Private collection

Responding to the circumstances of the New Economic Policy, the emergence of a new entrepreneurial class and a new consumer in Soviet Russia, Popova also produced designs using symbolic form, such as the five-pointed star of the Red Army (which she delineated in red within a black circle)33 or the hammer and sickle, the insignia of the new state, symbolising the unity of worker and peasant (fig.10). Using such images reinforced the Communist message, while also meeting consumer demand for more figurative motifs. Yet Popova drastically reduced the descriptive quality of these objects, simplifying them and stressing their underlying geometry. Hence, in her hammer and sickle design, the sickle is rendered in red as merely a portion of a circular line attached to a small, thicker line, while the hammer is drawn as a blue line topped by a blue quadrilateral. In this way, these essentially figurative elements have been geometricised, which is particularly evident if this design is seen within the context of the more descriptive renditions of tractors, planes and red stars that were prevalent in textile designs of the 1920s.34

In 1924, the writer and theoretician Osip Brik eloquently summarised the ideas and objectives of the whole of the constructivist engagement with textile design. In his article, which appeared the avant-garde journal Lef (Left Front of the Arts), he wrote:

A cotton print is as much a product of artistic culture as a painting, and there is no basis for drawing a dividing line between them. Moreover … the conviction is growing that painting is dying, that it is inseparably linked with the forms of the capitalist system and its cultural ideology, and that textile design has become the focus of creative concern – that the textile print and work on the textile print is the height of artistic work.35

Not surprisingly, therefore, Popova’s colleagues at Lef, notably Rodchenko and Stepanova, included numerous fabric designs in her posthumous exhibition of December 1924.36 These designs did not outnumber or supplant the paintings, but complemented them. The presence of a few select designs indicated the way in which the strong visual explorations of her paintings had been translated into the small-scale format of textile designs to produce fabrics that were used (and could be used further) by ordinary Soviet women for their everyday clothing.

Fig.11

Anonymous

Photograph of a Procession in Nizhny Novgorod 1899

The great variety of Popova’s designs and the scale of the different motifs used are evidence of the fact that she wanted to create fabrics to suit Soviet women from all walks of life, residing ‘both in the countryside and in the worker districts.’37 Clearly, in creating her textiles, Popova was strongly influenced by the urban and technological emphasis of constructivism and the abstract or objectless language of her own paintings. Yet she was also concerned to anticipate ‘the personal taste of the peasant woman in Tula’.38 In fact, geometric ornament had always been one component among many others of peasant dress (fig.11).39 In this sense, one could argue that in applying the lessons and concerns of her painting to fabric design, Popova was not just embracing a constructivist ethos, she was also revitalising a Russian peasant tradition.