This collection was amassed over a forty-year period by the photographer, graphic designer and author David King (1943–2016), who travelled and collected extensively in the Soviet Union, Europe and the USA. King’s collection provided the inspiration and visual content for his published works, which owe much of their appeal to the quality of the material, the author’s own experiences and the unique manner in which King created his books. This article will look more closely at David King’s approach to collecting and book production.

Fig.1

Stalin stands with a group of delegates at the Fourteenth Party Conference in April 1925.

Left to right: Mikhail Lashevich (suicide 1927); Mikhail Frunze (died 1925); Nikitich Smirnov (shot 1936); Alexei Rykov (shot 1938); Kliment Viroshilov (died 1969); Stalin; Nikolai Skyrpnik (suicide 1933); Andrei Bubnov (died in Gulag 1940); Sergo Ordzhonikidze (suicide 1937); Josef Unschlicht (shot 1938).

David King Collection (TGA 20172/2/3/2/306)

Fig.2

The same photograph reproduced in 1939 and retouched to leave only Frunze and Stalin’s close friends Voroshilov and Ordzhonikidze.

David King Collection (TGA 20172/2/3/2/307)

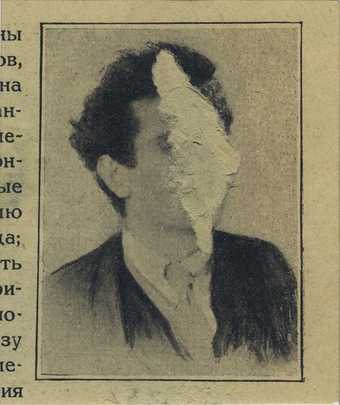

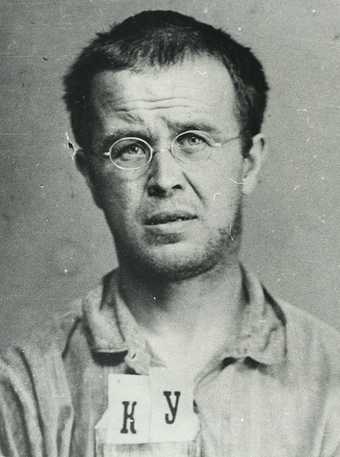

David King made his first visit to the Soviet Union in 1970 to gather material on Lenin for a Sunday Times Magazine feature that would mark the centenary of the revolutionary’s birth. There was plenty of related material to be found, and no shortage of assistance in finding it. King established contacts, visited archives and brought back large quantities of material for the feature. During the same visit King made enquiries about material relating to the Bolshevik revolutionary Leon Trotsky but, though the latter one of the most important figures of the Russian revolution, there was no material to be found anywhere. Staff at photo archives pleaded ignorance or claimed they had nothing on those of ‘little importance’. Trotsky had been expelled from the Soviet Union in 1929, and was later assassinated in Mexico in 1940 on Stalin’s orders. As with all those condemned, exiled or executed during Stalin’s reign, the memory of Trotsky was supressed as if to deny he had ever existed (figs.1 and 2). Fear of the secret police was so strong that the population censored their own holdings, throwing away, cutting out or erasing anything that bore the image of the condemned (figs.3 and 4). Although it was many years after the deaths of Trotsky and Stalin, King was still only able to collect the imagery from official and private sources, which the current regime wanted people to see. An admirer of Trotsky, King wanted to return Trotsky and others to their rightful place in the historical record and his collecting of photographs and memorabilia was a means of doing this.

Fig.3

Image of Leon Trotsky from the photographic album ‘History of the All-Union Communist Party’ (1874–1917) defaced by the album’s owner. Trotsky had been a focus of opposition forces to Stalin before his exile from the Soviet Union in 1929, and eventual assassination in Mexico in 1940.

David King Collection (TGA 20172/2/3/2/226)

Fig.4

Image of Gregorii Zinoviev from the photographic album ‘History of the All-Union Communist Party’ (1874–1917) defaced by the album’s owner. Zinoviev had been a party member since 1901 and a close friend of Lenin, he was executed along with many other ‘old Bolsheviks’ after the first Moscow Show Trial in 1936.

David King Collection (TGA 20172/2/3/2/232)

There were many obstacles to overcome when collecting in the USSR, not least the dangers involved in taking material out of the country. Any foreigner with quantities of photographs in their possession during the Cold War came under immediate suspicion and King had many close shaves. This period was fruitful for King’s collecting in other respects. As one of very few western collectors searching for material in the Soviet Union, he was able to acquire quantities of material from photographers, artists and designers whose work was ‘highly-skilled but often anonymous, … little known or long forgotten. In Stalin’s Russia, the applause could still be ringing in a person’s ears as they faced the firing squad.’1

Many of those who lost their lives during Stalin’s ‘Great Purge’ were posthumously rehabilitated under Nikita Khrushchev and successive Soviet leaders, but Trotsky would only be partially rehabilitated under Gorbachev in the late 1980s, after reforms had ushered in a new period of ‘openness’. Following these reforms King visited the Soviet Union much more frequently and collecting became easier as more and more material emerged. Photographs, books and artwork which featured, or were the creations of, political ‘undesirables’ owed their survival to the bravery of those who had hidden them from the authorities. King was able to purchase, for example, an original conté drawing of Trotsky that had lain hidden for over fifty years, pasted into the back of a picture frame by the artist Sergei Pichugin after Trotsky had fallen from favour. The KGB opened its archives to the public for the first time and within the gloomy aisles of the archive lay thousands upon thousands of neatly stored files and photographs of the victims of the Soviet state (figs.5–8). King was able to photograph thousands of these images and would use them to illustrate the human tragedy of Stalin’s regime in his book Ordinary Citizens, published in 2003.

Fig.5

NKVD (secret police) arrest photograph of Lydia Dzbanovskaya-Shtokvish, born 1888, accountant. Arrested 26 April 1937, on a charge of participation in the attempted assassination of Lenin in 1918, shot 27 September 1937.

David King Collection (TGA 20172/2/4/2/88)

Fig.6

NKVD arrest photograph of Alisa Venglosh, born 1887, German citizen, actress. Arrested on 22 July 1937 at the Savoy Hotel, Moscow on a charge of espionage, shot 16 August 1937.

David King Collection (TGA 20172/2/4/2/77)

Fig.7

OGPU (secret polic) arrest photograph of Konstantin Kurochkin, born 1898, head of laboratory at a meat canning factory. Arrested 7 July 1930, on a charge of industrial espionage (‘wrecking’), shot 24 September 1930.

David King Collection (TGA 20172/2/4/2/38)

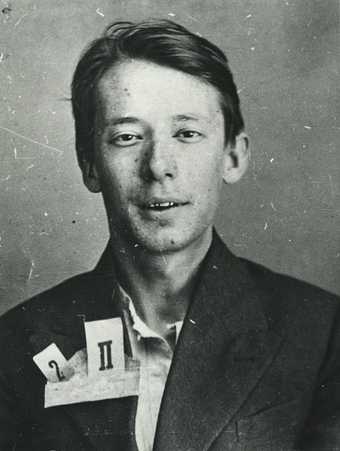

Fig.8

NKVD arrest photograph of Yevgeny Polyakov, born 1910, translator. Arrested on 22 August 1932 on a charge of being a member of a white guard terrorist organisation, shot 20 March 1933.

David King Collection (TGA 20172/2/4/2/47)

Despite the new spirit of ‘openness’ in the final years of the Soviet Union, King still had difficulty in procuring undoctored historic photographs; the reforms could not bring back all the imagery that had been destroyed or manipulated. For undoctored imagery King was forced to find material in the West. During the 1920s and 1930s the Communist International (Comintern) had flooded western nations with enormous quantities of photographs, pamphlets, magazines and books to showcase the success of the world’s first workers’ state. When the individuals featured in this material were interned or executed during Stalin’s purges, the Comintern could not doctor or destroy the material it had earlier distributed across Europe. In the 1970s and 1980s King was able collect this now unwanted material from second-hand bookshops, news agency archives and a network of private individuals. King’s contacts included individuals who had once been or still were active in the European political left or had even been members of Comintern. For instance, King was able to establish contact with Max Shachtman (1904–1972), who had been a key figure within the opposition to Stalin in Europe, and for a time the custodian of Trotsky’s archive.

Stalin’s legacy cast a shadow over the European left long after his death in 1953. King found that certain individuals in Europe, as in the Soviet Union, refused to acknowledge even the existence of Trotsky and his supporters. Nevertheless, through his extensive network King was able to overcome this difficulty; the hundreds of different stamps and labels on the backs of photographs in his collection evidence the breadth of his sources. Having access to imagery from both sides of the Iron Curtain meant that King could compare original images with doctored versions and was able to see the various methods of falsification which Stalin’s regime had employed. These comparisons would form the basis for King’s ground-breaking work The Commissar Vanishes (1997), which combined material gathered from the Soviet Union and from the West to expose the Soviet Union’s skilful distortion of visual media.

The design of King’s books reflects his own graphic design work and his interests in Soviet visual culture. After leaving the Sunday Times in 1976, King designed posters and leaflets for a variety of left-wing political groups and campaigns, including the Anti-Nazi League and the Anti-Apartheid Movement. His designs were influenced by the work of Soviet designers, such as Aleksandr Rodchenko and El Lissitzky, and used an interplay between bold text and simple shapes. King created his poster designs by hand, using scissors and glue, and he carried across this physical approach when he began creating his own books. Once he had decided on a theme and drafted a text, he would trawl through his collection to select the imagery and objects which would best illustrate each theme. The material was placed onto gridded sheets representing each page in a book and were lain side-by-side on the floor of King’s Islington studio. In this way he could play around with the visual flow of the book (he had floorspace to lay out half a book’s pages at once). He then decided on the best way of using the imagery. He had made a name for himself as the art editor at the Sunday Times Magazine in the 1960s, and he loved to experiment: he blew up tiny prints to fill a full double page spread or shrunk a poster to thumbnail size. His assistant Judy Groves worked with David King for over twenty years and has described him as being ‘filmic’ in his approach, always thinking in terms of close-ups and long-shots, and how each image (or scene) worked with the next.2 He would scan each item to various sizes and crops, and once again lay these out onto the gridded sheets laid on the floor in sequence. Once happy with each spread, the scans would be taped down and the pages annotated with instructions for the printer. The text would then be arranged and taped into place. The layouts were then given to the printer, along with the original images.

King’s experiences of collecting material in the Soviet Union, with the associated risks of arrest, were deeply challenging and frustrating, but his courage in overcoming these difficulties imbues the collection with personal value. As important to King were the stories of the owners’ experiences of suffering, sacrifice, and bravery in the face of terror. Many of these reflections of ordinary citizens might have been lost forever without David King’s work and, in this respect, it is no exaggeration to consider him as one scholar in the field of Russian studies commented, ‘a one-man archaeological expedition into a lost world’.3

The David King Collection (TGA 20172) and David King Library Special Collection (DKC) are available to consult at the Tate Library and Archive, Tate Britain.