This essay on Sheba Chhachhi’s Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91, printed 2014, traces and analyses the history of the work’s making, publication, exhibition, reconfiguration and acquisition by Tate. The account I produce here will certainly intersect, and even overlap, with the analyses of this work by other contributors to this In Focus publication who also read Seven Lives and a Dream (hereafter Seven Lives) within lineages of documentary, women’s activism and studio photography. My own archival and object-based inquiry is supplemented by two recently conducted interviews: the first with Chhachhi at her studio in New Delhi on 25 February 2018, and the second with Nada Raza, formerly Assistant Curator and Research Curator at Tate Research Centre: Asia, which was held on 20 September 2018 at Tate Modern, London.

Drawing on these primary sources, I hope to provide a richer understanding of how the images in Seven Lives have been excavated, augmented, organised and displayed over time. I will explore specifically how this work has been configured in a way that harnesses the artistic, spectatorial and discursive potential for social documentary photography to destabilise essentialist readings and unravel entrenched codes and stereotypes of representation. This has been a gradual and staged process, from the early 1980s, when the images for Seven Lives were first shot, taking the anti-dowry agitations in New Delhi as their subject and the women’s movement as their audience; to 2016, when a carefully designed photographic installation of select images was shown in Tate Modern’s permanent collection galleries during the opening of its new building.

Activism and image making

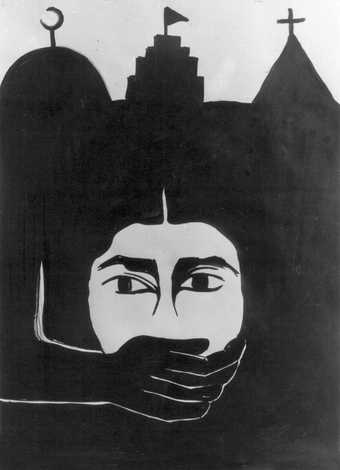

Fig.1

Lifetools (Sheba Chhachhi and Jogi Panghaal), for Saheli Women’s Resource Centre

All Religions are Patriarchal mid-1980s

Poster

Available for use without permission, with appropriate credit

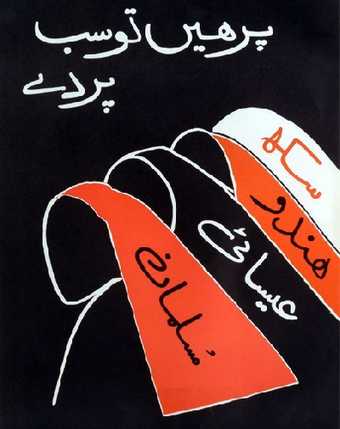

Fig.2

Lifetools (Sheba Chhachhi and Jogi Panghaal), for Saheli Women’s Resource Centre

Hindu, Muslim, Sikh or Christian: The Veil is the Same mid-1980s

Poster based on an original drawing by a local group

Available for use without permission, with appropriate credit

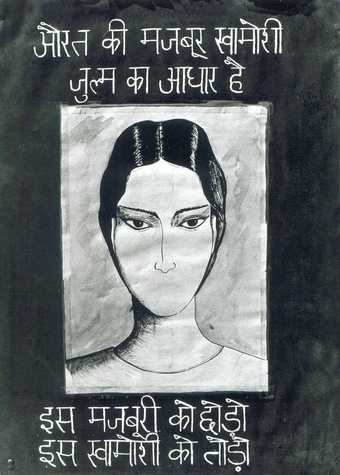

Fig.3

Sheba Chhachhi

Women’s Enforced Silence is the Basis of Violence: Break the Silence early 1980s

Poster

Available for use without permission, with appropriate credit

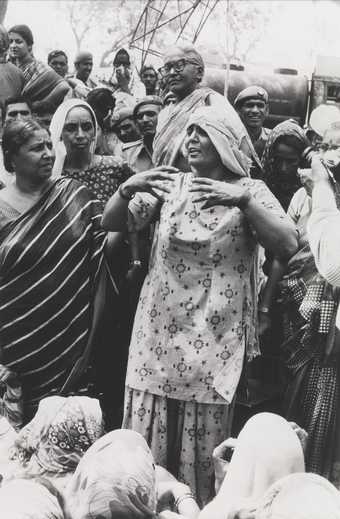

Fig.4

Sheba Chhachhi

Shardabehn – Public testimony, Police Station, Delhi 1988, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

776 × 519 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

In its basic structure, Seven Lives consists of two sets of images made over the course of a decade. The first set of photographs were taken at women’s movement demonstrations around Delhi throughout the 1980s. The second set are portraits created in 1990–1 in collaboration with seven of the movement’s activists, in settings of their choosing. The trajectory of these images closely parallels the intellectual investments and activist involvements of their maker. Chhachhi graduated in economics from Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi University in 1977, then studied media and society at Chitrabani in Kolkata and visual communication at the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad. Returning to Delhi in 1980, she jumped headfirst into the women’s movement, which had mobilised strongly around the issue of dowry and related domestic violence.1 Her activism was directly fuelled by her education, from a critical engagement with media at Chitrabani that first raised questions about the power relationships and ethics of documentary photography, to the camera and darkroom skills she acquired at NID. Her sister Amrita Chhachhi, a feminist scholar and activist, was deeply involved with the women’s movement, and new groups including Stree Sangarsh and Saheli Women’s Resource Centre were being set up.2 Sheba Chhachhi began attending meetings, discussions and street theatre performances – notably of the play Om Swaha, about the dowry-related killings of two women in Delhi, scripted and directed by Maya Krishna Rao and Anuradha Kapur, and first performed in 1979.3 At marches, protests, performances and public actions, Chhachhi took on the role of documentarian and designer, photographically recording the events and working with other women to create posters and pamphlets to be displayed and handed out (figs.1–3). Histories of the movement, notably Radha Kumar’s The History of Doing (1993), include a large number of Chhachhi’s images from the period.4 In Kumar’s book, the chapter titled ‘The Campaign Against Dowry’ is richly illustrated with pictures of posters and handheld signs in Hindi and English, alongside photographs showing groups of protestors marching with the signs in Delhi.5 Chhachhi’s image of Shardabehn giving public testimony outside a police station, included in Seven Lives, is also reproduced in The History of Doing, where Shardabehn is identified as ‘a member of the audience’ rather than by name (fig.4).6 It is significant that a subsection of Chhachhi’s images underscores the participation and voices of specific individuals within the collective movement, laying the ground for the later manifestation of the work in which she created a multi-part portrait of seven individuals on the frontlines.

In addition to photographic documentation of the women’s movement created by both participants and journalists, the body of visually inventive posters and ephemera that were collectively workshopped and economically produced by movement members remains in various organisational and personal archives. A large number of them have been collected and published online by the feminist publishing house Zubaan as part of its Poster Women project.7 The collaborative nature of these endeavours and their role in building feminist networks and solidarity across South Asia, involving significant cultural and academic figures such as Chandralekha, Sadanand Menon, Dashrath Patel, Rajini Thiranagama and Lala Rukh, is only beginning to be understood.8 Prior to the fragmentation of the movement during the 1990s into discrete organisations targeting specific issues (colloquially referred to as ‘NGOisation’), these transnational networks of support and exchange were built and maintained through the generous contribution of time, skills and monetary resources by individuals. From her own experience, Chhachhi recalls the high cost of analogue photography, which meant she occasionally had to delay processing, was not always able to make contact sheets, and had to purchase film in bulk and unspool it.9 While these constraints were overcome with resourcefulness and effort, working in analogue also demanded a degree of thought, discernment, focus and judiciousness that is altogether missing from digital image making. Chhachhi’s photographs – both those from the frontlines and the staged portraits – reveal a sophisticated sense of timing, composition and framing, and attest to her personal involvement with the subjects, the movement and feminist ideas of subjecthood, performativity and politics.

As a Delhi-based artist-activist from a Sikh family, Chhachhi’s relationship to both activism and image making was transformed by the anti-Sikh pogrom of 1984. While on the streets and fighting for the rights and protection of the vulnerable, Chhachhi herself came under threat from the murderous mobs that fanned out across the city, killing Sikhs and destroying their property. In the immediate aftermath of those events she joined the Nagrik Ekta Manch (Platform for Citizens’ Unity), which provided shelter and aid to those affected by the violence. Within the context of this relief effort, a number of volunteers including Chhachhi initiated a low-cost, easily portable exhibition addressing the causes of violence, specifically the political complicity and premeditation that allowed such events to unfold in the nation’s capital. Hand-drawn black and white posters were hung with clothes pegs on strings and travelled from college to college within Delhi in an effort to hold the ruling Congress party accountable for inciting and enabling the violence. A sense of unease and eventually open disagreement erupted within the ranks of the Nagrik Ekta Manch, with a large number of participants finding this exhibition initiative too overtly political and at odds with their conception of volunteering to perform humanitarian relief work. Meanwhile, the exhibition also provoked outrage among some viewers and met an unfortunate end at a Delhi University college, where it was brutally ripped up. The latter half of the 1980s was coloured by these developments, which Chhachhi described as a significant part of her (and her peers’) political education. The fate of the travelling exhibition and the experience of negotiating fissures and conflict in the context of a citizens’ response group with diverse agendas compelled Chhachhi and her interlocutors to further interrogate the politics of representation as well as the increasing mediatisation and varied reception of activist imagery. During the same period, not coincidentally, the women’s movement also began addressing questions of identity along caste, class and religious lines, a focus that persisted throughout the 1990s.10

At the level of the image and its circulation in both popular and activist media outlets, Chhachhi was confronted with a situation in which representations of the struggling, protesting, militant woman had become a visual trope. Arriving slightly early for a protest one day, she found press photographers directing women to pose and shout slogans for their cameras. The resulting images, resembling her own from the early 1980s, were now appearing in mainstream newspapers that had not previously devoted coverage to the activities of women’s groups. The intrinsically unstable nature of the documentary images was further challenged by their blatant staging and manipulation. An aesthetic counter-current emerged with the increasing proliferation of video within activist circles: a younger group of feminist filmmakers and theorists (of which Chhacchi was not a part) came together in 1985 at the AJK Mass Communication Research Institute, Jamia Milia Islamia, to form the collective Mediastorm. In the years following, they were able to produce and distribute three films independently: Secular India (1986), From the Burning Embers (1988) and Whose Country is it Anyway? (1991). Meanwhile, the women’s movement was undergoing a period of restructuring into NGOs of various scales, as mentioned earlier, and many of those who had been active participants in the early 1980s retreated into a phase of research and reflection. For Chhachhi, concerns about the appropriable nature of the documentary image, and unease around the relationship between the photographer and photographed, prompted her to revisit her own images of the movement and consider them in a different light. Many of the women she had photographed were close friends – they had planned interventions and marched together across class and community lines. She had documented their public face and actions on the frontlines of the movement, and the iconicity those images had achieved in newspapers, magazines and broadcast media now threatened to foreclose and trivialise their reception. Chhachhi grappled with the idea of capturing the complexity and difference of individual personalities as they operated both within and outside the movement, a preoccupation that brought her, in 1990, to the idea of making multi-part staged portraits in collaboration with her closest comrades.

Each of these portraits was created through a sustained conversation between the photographer and the woman portrayed. Initially Chhachhi invited eight women – four working class and four middle class – to be photographed, but the collaboration with one of the middle class women did not materialise as hoped, and Chhachhi later attributed the ‘dream’ in her title to both this missing portrait and the larger unachieved ideal of women’s empowerment and liberation.11 Drawing on the method of individual storytelling in a collective context, which was a well-established mode of sharing within the women’s movement, each protagonist chose objects of significance to their story to create a mise-en-scène that performed their narrative for the camera. Each set of portraits pertaining to an individual activist took about three months of back-and-forth to make. The subjects continued to be involved after Chhachhi shot the images, weighing in with comments and objections upon seeing the results, which Chhachhi shared by printing selections from her contact sheets, then photocopying them and enlarging the photocopies. For example, the composite portrait of Shahjahan – a working class mother from West Delhi whose daughter was murdered over dowry – was initially situated at a Mughal monument, a favourite of both photographer and photographed, but when Shahjahan saw the images she did not think they told her full story. This led them to relocate to her modest home, with shelves of steel utensils and her sewing machine as the backdrop, and a miniature version of the house she had crafted from a shoebox placed next to her on the bed. Chhachhi recalls that the middle class women had a far harder time constructing their image for the camera.12 Having been photographed all their lives, they resisted the provocation to stage themselves, entrenched as they were in a rather conventional (even inaccurate) understanding of documentary imaging as a record of something or someone as they appear in the world.

Early exhibitions

Chhachhi’s images of the women’s movement from the early to mid-eighties were first shown in an art gallery in London during the 1988 edition of the Spectrum Women’s Photography Festival. As part of the festival, British-Indian photographer and curator Mumtaz Karimjee organised a show titled Four Indian Women Photographers, which included Sooni Taraporevala, Ketaki Sheth, Purnima Rao and Chhachhi, all of whom were based in India. The exhibition took place at Horizon Gallery, an important venue for British South Asian artists that was located on Marchmont Street in Bloomsbury and operated from 1987 to 1991.13 Chhachhi remembers having grave doubts about putting her images from the movement in a white cube gallery space, but Karimjee, a fellow feminist and artist working at the intersection of diasporic and queer communities in Britain, convinced her of the importance of presenting an alternative view of women and photographic practice in India. The exhibition drew many young members of the South Asian diaspora who, on viewing the photos, Chhachhi recalls, identified women that looked like their mothers but were in fact at the forefront of the fight against oppressive patriarchal structures.14 A number of discussions and meetings took place in the gallery during the run of the exhibition, establishing a new audience and set of interlocutors for the body of images.

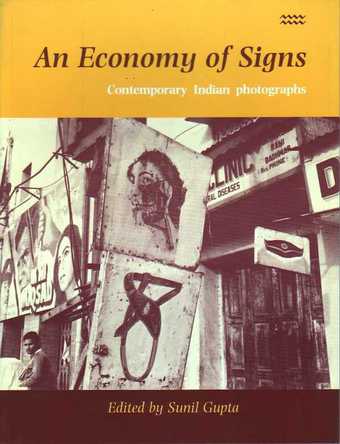

Fig.5

Front cover of Sunil Gupta, An Economy of Signs: Contemporary Indian Photographs, exhibition catalogue, The Photographers’ Gallery, London 1990, featuring Ram Rahman, Delhi 1989

The staged portraits that make up part of Seven Lives were also first shown in London, where the discourses and spaces established by the British Black arts movement since the early 1980s provided a context for the questioning of identity, representation and reception. The photographer, activist and curator Sunil Gupta included Chhachhi’s portraits in an exhibition titled An Economy of Signs: Contemporary Indian Photographs at The Photographers’ Gallery in 1990 (fig.5). Like Karimjee’s 1988 show, this exhibition also presented the work of photographers living in India to a London audience, though the selection of artists was not limited to women. A review published in Third Text that was generally critical of the exhibition’s framing of ethnicity and difference described Chhachhi’s images as ‘a corrective to the delicate and passive Indian female beauty frequently depicted by the West’.15 Chhachhi’s own contribution to the exhibition catalogue, titled ‘Feminist Portraiture’, reveals how she attempted to disrupt the proliferation of such stereotypical imagery and trouble the essentialising tradition of portraiture through the collaborative creation of multi-part, open-ended and contingent representations of each subject. She writes,

These women are plural, contradictory, multiple. Any one image excludes the other; why should one choose a particular photograph, privilege one over the other? I am attempting to build composite images of these women, sometimes, but not always, including earlier photographs – each woman seems to demand a somewhat different constellation so the structure of each portrait varies, as do the women themselves.16

Fig.6

Sheba Chhachhi

Radha – Staged Portrait, Anandlok, Delhi 1991, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

790 x 517 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Fig.7

Sheba Chhachhi

Shahjahan Apa – Staged Portrait, Nangloi, Delhi 1991, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

785 x 521 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

This publication (and the exhibition) included two portrait clusters from Chhachhi’s large archive of images shot between 1980 and 1990, corresponding to two women who were selected to present different ends of the class spectrum within the feminist movement. The first, Radha, a young academic from an affluent South Delhi residential neighbourhood, appears in multiple images, reclining on a chaise longue or sitting among plants, books, activist posters, papers and framed family photographs (one of these images became part of Seven Lives; fig.6). The second, the aforementioned Shahjahan ‘Apa’,17 is pictured onstage and among fellow demonstrators but also in her modest house, tightly clutching her unworn burka and looking into the camera, while a disparate group of objects is neatly arranged on the bed behind her: a photograph of her with a microphone addressing a gathering (also taken by Chhachhi), a jhola or cloth bag, and a sewing machine. A different staged portrait in the same setting, from 1991, is included in Seven Lives and a Dream. Here, Shahjahan sits on the bed, the burqa draped across her lap and left arm while three of Chhachhi’s photographs of her from the movement rest against her legs, occupying the image’s foreground. Beside her is the model of a hut constructed from cardboard while the sewing machine is tucked into a niche in the wall behind (fig.7).

Fig.8

Wild Mothers I: The Wound is the Eye 1993

3 terracotta sculptures, 9 terracotta tablets, hand-tinted silver gelatin prints, found images, turmeric, pigment and sand

3500 x 2100 x 2500 mm

Collection of the artist

© Sheba Chhachhi

Image courtesy the artist

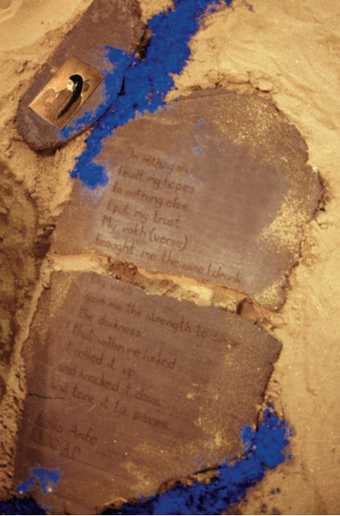

Fig.9

Detail of Wild Mothers I: The Wound is the Eye 1993

© Sheba Chhachhi

Image courtesy the artist

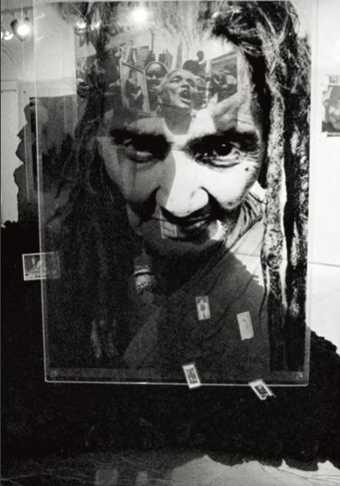

Fig.10

Wild Mothers II: The Mirror is the Witness 1994

21 black and white film positives, terracotta sculpture, stone fragments with text, coal, found images and reflective polyester film

1500 x 900 x 3500 mm

Collection of the artist

© Sheba Chhachhi

Image courtesy the artist

Fig.11

Wild Mothers II: The Mirror is the Witness 1994

© Sheba Chhachhi

Image courtesy the artist

After the gallery showing in London, Chhachhi continued presenting the portraits across diverse contexts in India. She included them in a slideshow accompanying a paper she presented at the Indian Association for Women’s Studies Fifth National Conference at Jadavpur University, Kolkata (9–12 February 1991), and as a pop-up exhibition alongside a seminar on women’s narratives at the India Habitat Centre that continued at the art gallery of Alliance Française, both in New Delhi. In this exhibition, responding to the seminar’s focus on narrative, Chhachhi juxtaposed the images with free-flowing fabric and an associative loop of words culled from her subjects’ field notebooks.18 Chhachhi’s work combining text, textile and images was followed by her first large-scale installation, Wild Mothers I: The Wound is the Eye 1993 (figs.8 and 9), which employed archival and documentary photographs of female saints, poets and ascetics – the latter of whom she had spent a great deal of time with and photographed since her student days in Ahmedabad.19 The early 1990s also saw the publication of a significant body of feminist scholarship and translations, into English, of a large corpus of writing – with radical, proto-feminist strains – by subcontinental women from diverse, heterodox traditions.20 Deeply immersed in this literature and the politics of its writers, and channelling her recent experiments with clay at Andretta Pottery and the Free Academy, The Hague, Wild Mothers I resembled an archaeological site, featuring sand and terracotta sculptures embedded with images.21 In the following year, 1994, Chhacchi continued to expand her installation-based practice in an exhibition at the Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan in New Delhi. Bringing together three bodies of work – images from the frontlines of the women’s movement in the 1980s, the staged portraits and the photographs of female ascetics – she created a layered presentation by printing the images on film positives, which rendered them translucent. She titled this work Wild Mothers II: The Mirror is the Witness 1994 (figs.10 and 11) and gave it the form of an ellipse with reflective material on the floor. The viewer, whose reflection added another register to the work, could move around the installation, with each vantage point producing a different permutation of the layering between images from the different series. The performative aspect of all figurative camera imagery was foregrounded, putting into dialogue three sets of pictures that represented women seeking personal and societal transformation across spheres of civil society, religion and spirituality.

In the catalogue for ‘An Economy of Signs’, Sunil Gupta describes Chhachhi’s early 1980s images of the women’s movement as ‘positive images’ in a ‘classical documentary style’.22 Recognising the shift in Chhachhi’s practice at the end of the decade, he contextualises it as part of the broader discourse of postmodern feminism wherein the ‘representation of politics (positive images)’ gave way to a critical engagement with ‘the politics of representation’.23 Of Chhachhi’s specific experience working through questions of documentary vision, Gupta writes,

Chhachhi, moving from one position to the other, continues to question the validity of singular modes of seeing, demonstrating the pressures placed on Indian photographers to come to terms with their medium without having the support of critical theory provided to their counterparts within the West.24

Chhachhi’s shifting positions, as she negotiated questions of representation emerging at various points during her academic training, professional practice and engagement with activist and artistic peers, produced responsive reconfigurations of her work with image and text. Installation provided a mode of subjective spectatorship that brought together various strands of her thought and practice into a spatially contained constellation of parts. Sculpture, text and image together generate complex, non-determinative readings by extending the temporality and terms of spectatorial engagement with the work. Neither socially engaged graphic design nor documentary photography appear to have provided Chhachhi with sufficient conceptual room to expand her visual practice. Meanwhile, a certain section of the contemporary art world – in the wake of debates around postmodernism, globalisation and the proliferation of biennial exhibitions in the 1990s – was becoming increasingly hospitable to work from across media and spheres of professional activity.25 Chhachhi’s transition into the spaces of contemporary art occurred with the staged portraits of the early 1990s, which critically probed identity, subjectivity, performativity and representation. In the decades since, she has become widely known for multi-media installation work as well as public art interventions.

Revisiting the archive

Fig.12

Sheba Chhachhi

Installation view of Record/Resist 2012 at the 9th Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, 2012

Photo-video installation, 21 black and white digital archival prints and 17 min video loop

Collection of the artist

© Sheba Chhachhi

In 2011, Nancy Adajania was appointed as one of six women Artistic Directors of the 9th Gwangju Biennale, which was to take place the following year. Her subsection of the larger exhibition, titled Logging In and Out of Collectivity, raised a crucial question: ‘What sort of bridge can the figure thus far known as the artist build between the domain of symbolic action, institutionalized as culture, and the arena of practical, productive politics?’26 Adajania situated her curatorial endeavour in the lineage of the ‘discursively oriented biennial’, beginning with the 1989 edition of the Havana Biennial, then significantly articulated by Documenta X (1997) and Documenta XI (2001). She writes, ‘[T]he discursively oriented biennial embodies the hope that the discourse generated can leak outward from the art world to form communicative engagements with the arenas of civil activism and political protest.’27 Within this context, Adajania invited Chhachhi to revisit her archive of images from the 1980s and 1990s, provoking her to consider the question of sustainability in activist movements. For Chhachhi, returning to this material made evident the impossibility of simply sharing it as archival work, thereby catalysing the creation of a new installation. Record/Resist 2012 is a photo-video installation in which twenty-one black and white digital archival prints of images from the women’s movement as well as the staged portraits are suspended from the room’s ceiling at various levels (fig.12). Projected on the floor below them is a seventeen-minute video loop, a crucial component of the installation that annotates the images with Chhachhi’s recollections and reflections on the movement and the present conditions for protest and activism. This critical annotation draws out the politics embedded in the photographic archive, which need to be articulated and underscored in light of the historical images’ ‘semantic availability’, as photographer Allan Sekula puts it.28 In other words, Chhachhi’s contemporary intervention into the archive-based installation allows for a necessary re-politicisation of photographic meanings that would otherwise remain up for grabs. While the historical photographs remain open to reproduction and rearrangement, the installation format allows Chhachhi to carefully orchestrate their organisation and narrative, bearing in mind the divergent temporalities and contexts of making, archiving and spectatorship. Viewers are encouraged to walk through the work, with sightlines shifting as they move between and around the images and video, producing a montage-like experience and relating back to the mode of spectatorship invited by her initial installation of these images in 1994 as part of Wild Mothers II.

While working on the video for Record/Resist in 2011, Chhachhi was invited to contribute to the publication Making a Difference: Memoirs from the Women’s Movement in India, edited by feminist writer and publisher Ritu Menon.29 Much like the video, the image-text piece that Chhacchi produced, titled ‘Moments, Contradictions, Transformations’, is a self-reflexive memoir of the women’s movement and its afterlives. Of singing protest and solidarity songs at the recent funeral of a close comrade, she writes,

An almost forgotten self rises as I call out the chant – flushed with the energy, the weight, the warmth and the power of singing together, chanting together. What I took for granted in the ’80s and ’90s, becomes rare and precious in 2011.30

In the video Chhachhi laments the absence of public spaces for protest in New Delhi – the national capital – since the 1980s, restricted as they now are to a relatively small area, Jantar Mantar, close to the Indian Parliament. Opening in September 2012, the Gwangju installation preceded by just three months the massive protests in the city following the rape and murder of Jyoti Singh Pandey, which once again occupied the vast grounds around India Gate. For decades, this had been an important site for public agitation, the loss of which was marked in Chhachhi’s Record/Resist by ghosts of demonstrations passing through the monument’s lawns.

During these events in December 2012, Chhacchi was struck both by the scale and energy of the protests and the disconnect with feminist history and thought as a younger generation of men and women, angered by the brutality of the Pandey case, called for the death penalty and chemical castration of rapists. In an attempt to generate an intergenerational activist dialogue, Chhachhi was determined to bring her Gwangju installation to New Delhi. Interestingly, though many activist spaces were keen to host the work, they were only able to offer up their modest premises for a few days. Chhachhi’s installation, conceived for an art gallery and therefore requiring certain spatial dimensions, lighting conditions, projection facilities and installation time, could not easily or sensibly be shown in any of the available activist spaces. With this in mind, she approached the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA) and began a conversation with the curators of an upcoming exhibition, Zones of Contact: Propositions on the Museum. The curators agreed to include Chhachhi’s Record/Resist and the exhibition opened at the museum’s Noida site in January 2013.31 In March that year, during the run of the exhibition, Chhachhi organised a public discussion at KNMA, inviting those who had been part of the women’s movement in the 1980s and those who were active in it (and allied causes) during the present.

Coinciding with the museum showing of Record/Resist, Chhachhi’s Mumbai gallery, Volte, showed a selection of prints from her series on the women’s movement and women ascetics at its India Art Fair booth in New Delhi (31 January – 3 February 2013). Chhachhi was very reluctant about these prints being shown in a fair, and on the gallerist’s insistence, had agreed on the condition that she would only entertain institutional interest in them. She believes these images belong in the public domain and would not agree for them to be sold into a private collection.32 Images from these series had also recently been shown in Mumbai, as part of two group shows at galleries organised by independent curators: Staging Selves: Power, Performativity and Portraiture, curated by Maya Kóvskaya at Sakshi Gallery (September 2011) and Your Name is Different There, curated by Nancy Adajania at Volte Gallery (December 2011). The latter exhibition had been seen by Tate’s Frances Morris (then Head of Collection for International Art) and Jessica Morgan (then Daskalopoulos Curator of International Art), who visited Mumbai in early December 2011 on a preliminary research trip leading to the setting up of Tate’s South Asia Acquisitions Committee. Morgan returned to India in January 2013 and saw the larger selection of images at Volte’s art fair booth. Following this visit, Tate expressed an interest in acquiring the work, and a conversation began between the artist, Morgan and Nada Raza, who was then Assistant Curator of International Art for South Asia at Tate.33

Configuring Seven Lives and a Dream

Chhachhi’s conversations with Tate took place at a time when Tate Modern’s collection and display strategy – led by Frances Morris – was focused on improving the representation of women artists from around the world. Simon Baker, then the photography curator at the museum, was developing a collection strategy specific to that medium, and in the process the distinction between documentary and art photography was being actively debated.34 Chhachhi’s images troubled these categorical distinctions, demonstrating a unique history of direct engagement with the women’s movement in India as well as the employment and unsettling of documentary photography’s conventions. Raza flags the staged portraits as crucial to the museum’s decision to seriously consider the work for acquisition, elaborating that understanding their context and process through conversations with the artist provided deep insight into Chhachhi’s thinking about agency and subjectivity in collaborative image making.35 Moreover, within the framework of the museum’s South Asia Acquisitions Committee – officially set up in 2012 – it was decided that artists would be researched and considered generationally, while emphasising broader regional coverage and cross-border connections to avoid a disproportionately strong focus on India.36 For Raza, the post-Emergency, pre-liberalisation moment in India – roughly spanning the 1980s and early 1990s – was a priority, given the number of visual artists catalysed by the political and social transformations of the period into diverse forms of engagement with politics and activism.37 Chhachhi’s work fell squarely within this framework, and had a deep resonance with the practice of fellow artist-activists in the region: Lala Rukh in Lahore is one example, and her work has also since been acquired by Tate (see Rupak 2016).

However, the configuration of Seven Lives for a museum collection required extensive discussions between the artist and curators on a number of issues. Until this point, as demonstrated in this essay, the images had been shown in many different combinations and formats, as a kind of ‘open work’ that changed with the site and context of display. Yet the artist and the museum were keen to establish an edition with specific parameters, which would provide both sides with a greater degree of control over the work’s future in terms of formal specifications and display possibilities. Baker, in keeping with museum policy, strongly preferred the acquisition of silver gelatin prints since that is how the images were originally printed in the 1980s and early 1990s.38 With this in mind, Chhachhi returned to her archive to configure and ‘close’ the work, producing Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91, a multi-part portrait of seven women with a total of nineteen images in clusters of two to four images per woman. Since only an incomplete set of silver gelatin prints existed at the time, the artist agreed to reprint the complete edition from her original negatives in 2014.

Despite its temporal and conceptual proximity to the video-image installation Record/Resist shown in Gwangju and at the Kiran Nadar Museum, Seven Lives is an altogether different work. It is designed to be displayed as a series of black and white prints on the gallery wall in a prescribed configuration. While the Tate curators were aware of the Record/Resist installation, which contained digital prints and a video projection that viewers could walk into and around, they had not seen it in person, and pre-empting concerns around conservation and visitor access, they continued to pursue the acquisition of the silver gelatin prints for Seven Lives.39 As per the artist’s specifications, the entire group of nineteen images does not have to be shown together, but a cluster corresponding to an individual activist cannot be broken into single images.

Fig.13

Installation view of Chhachhi’s Seven Lives and a Dream (left) alongside Artur Zmijewski’s Democracies 2009 (centre) and Theaster Gates’s Civil Tapestry 4 2011 (right) as part of the Artist and Society collection display at Tate Modern, London, 2016

© Tate

As part of the planning for the rehang of Tate Modern’s collection galleries to coincide with the opening of a monumental extension to the museum in 2016, Morris demanded a gender balance and a concerted emphasis on the inclusion of work by non-Western artists that had been acquired in recent years through the museum’s regional acquisition committees. Chhachhi’s entire series first went on display at Tate as part of that rehang, located in the Artist and Society section, where it shared a room with works by Artur Zmijewski and Theaster Gates (fig.13). Albeit ‘closed’ in terms of configuration, display guidelines and edition numbers, the images that constitute Seven Lives and a Dream were once again reinvigorated – decades after their making – by the possibility of new neighbours, viewers and interpretations in the galleries of a major metropolitan museum with an international collection and close to six million annual visitors.40