The ‘Revolutionary Capital: Algiers and its Global Reverberations’ panel with (left to right) moderator Natalie Melas, Yasmina Reggad, Elaine Mokhtefi and Anneka Lenssen, at Axis of Solidarity: Landmarks, Platforms, Futures, Tate Modern, 23–25 February 2019

Photo © Jacob Perlmutter

In the art world, solidarity is best understood when it helps change perceptions of humanity, when it is witnessed as action for and with others, when it reveals a conscious decision to support others, to stand by them as friends and allies. Political solidarity is a sacrifice; it asks that we share resources, that we share our time and energy. It can be painful, it can be fully tragic and joyful, it is an act that builds active friendship and promotes the best of our common human spirit.

– Gavin Jantjes speaking at Tate Modern, 24 February 2019

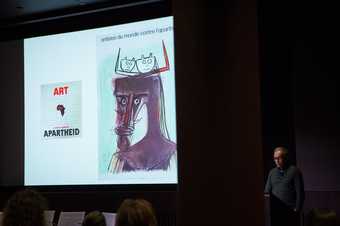

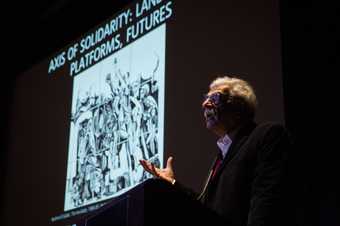

Artist and curator Gavin Jantjes presenting on ‘Solidarity Practiced: Seven Tales of Solidarity’ as part of the panel ‘Anti-Apartheid Solidarities – From South/ern Africa to Palestine’, at Axis of Solidarity: Landmarks, Platforms, Futures, Tate Modern, 23–25 February 2019

Photo © Jacob Perlmutter

In this hopeful reflection on the term ‘solidarity’, South African artist Gavin Jantjes captures the fervour behind the idea of transnational alliances. His statement, however, also highlights the unresolved aspirations and complex legacies of solidarities forged in the past century.

Attending the conference as a contributor, I presented alongside a range of scholars, artists, curators and activists whose work revisited landmark gatherings, organisations and movements which strived to challenge the notion of a single (post)colonial subjectivity from the 1960s to the 1980s. Focusing on the visual culture, cinema and literature which evolved during this period, the conference explored how liberation and collective struggles transcended political rhetoric. It also examined how art and writing emerged as convergence points between temporally and geographically dispersed groups, while defying any unified formal or aesthetic characteristic. Bringing academic voices together with those of artists and activists, the nine panels, three artist talks and two keynote lectures were structured around three themes – ‘landmarks’, ‘platforms’ and ‘futures’.

The first thematic grouping, ‘landmarks’, considered events and gatherings which marked the coming together of officials and cultural workers to discuss possibilities for political, economic, cultural and philosophical cooperation. These included the Tricontinental Conference held by the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL) in Havana, Cuba in 1966; the Algerian Revolution (1954–72); and the international iterations of anti-apartheid campaigns during the 1980s.

Emerging from these presentations was an investigation of ‘landmarks’ not only as historical events, but also as modes of transmission and (re)enactment. As observed by the current OSPAAAL Director, Rafael Enriquez Vega, the Tricontinental Conference was made possible by Cuba’s commitment to establishing an expansive ‘propaganda machine’ in the form of the Tricontinental bulletin and magazine, as well as posters, books, pamphlets, newsreels and radio programmes. The historical circulation and continuing influence of these materials underscores the role of national commitments to sustaining transnational communications. However, they also illustrated ‘solidarity’ as ‘performed iteration’, whereby collective forms of belonging and agitation are seen on an aesthetic level beyond the confines of the nation state.

This performative dimension of solidarity came under scrutiny in the first of the conference’s three artist talks. Naeem Mohaiemen reflected on his video-work Two Meetings and a Funeral 2017, in which he used footage of a speech delivered by S Rajaratnam, the Singaporean delegate to the 1973 Non-Alignment Movement Conference. In contrast to the long-winded rhetoric of other speakers, Rajaratnam went off-book to give more urgent reflections. Interlocuting with a quotation from Rajaratnam’s speech (‘I ask myself, to whom have we been communicating this past week? To ourselves or to the two billion people we are supposed to represent?’), Mohaiemen articulated the tension between solidarity as a state-driven venture and the impetus of individuals to work independently or collaboratively to rally behind a cause.

Manthia Diawara, Professor at New York University, delivering his presentation entitled ‘Meet Me in Bamako: The Birth of the Movement of the African Democratic Assembly (RDA 1946)’, at Axis of Solidarity: Landmarks, Platforms, Futures, Tate Modern, 23–25 February 2019

Photo © Jacob Perlmutter

This relationship between intention and iteration permeated the conference’s exploration of ‘platforms’. Opening with a discussion on the formation of the African Democratic Assembly in Bamako, Mali in 1946, Manthia Diawara spotlighted the prevalence of socialist and Marxist thought in a number of writings and gatherings of the time. This question of self-representation was further pursued in Christopher Lee’s examination of the visualisations of the 1955 Bandung Conference in Bandung, Indonesia. By asking whether the visualisation of solidarity resides in abstraction (conveyed via documentation) or the actual historical moment, Lee’s talk foregrounded discussions on the role of documentation and publishing as messengers of discourses on solidarity. Here, Elizabeth Harney’s discussion of the legacy of the journalist Simon Malley (1923–2006) via the journal Africasia emphasised the shift in journalistic culture towards promoting ‘self-to-self alliances’, highlighting the role of personal bonds and networks in reflecting evolving positions and subjectivities. The conference pursued this line of thought in more overtly visible connections, including the role of key organisational figures in exhibition-making: Mario Pedrosa’s vision for the Museum of Resistance in Chile, discussed by Isabel García Pérez de Arce and Alexia Tala; and Zoran Krajisnik’s mobilisation of his international networks for the Ljubljana Graphics Biennale (founded in 1955), presented on by Anthony Gardner. A more productive connection, however, emerged around modes of personal and collective outreach in publications.

Harney’s discussion of Malley led into my own consideration of the short-lived magazine Black Phoenix (1978–9), conceived by the London-based Pakistani artist Rasheed Araeen as a personal and artistic response to the failures to enact successful solidarities in London during the 1970s. This junction of individual and creative efforts also underpinned Sanjukta Sunderasson’s exploration of Lotus, the magazine of the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association. Sunderasson traced illustrations across Lotus’s multiple, multilingual registers and varying lineages of Afro-Asian experiences within the broader visual language of socialism. In a similar vein, Holiday Powers grounded the visual language of the journal Souffles within political and cultural developments in Morocco, and also contextualised the journal as part of wider efforts to convey pan-regionalism with North Africa and Palestine.

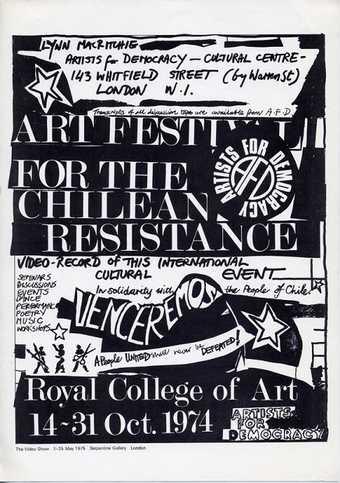

What emerged from these discussions was a tentative consideration of publications and exhibitions as archives of evolving consciousness and shifting bonds. They signalled that anti-colonial sentiments and activities do not exist coherently in the present – a notion also emphasised in the second artist talk by Chile-born Cecilia Vicuña. Opening with an evocative call to recognise the silenced and marginalised positions of indigenous peoples, Vicuña wove a thread across her early performative and painting practices in Chile, to her migration to London in the early in 1970s. It was in 1973 in London that she co-created Artists For Democracy (AFD), a cohort of artists and activists bound together by a commitment to liberation and leftist struggles. In her talk she described the Arts Festival for Democracy in Chile, organised by the AFD at the Royal College of Art in London in the wake of the military coup in Chile in 1973. Reflecting on the event, the artist offered a potent reminder that artist-activist platforms of the 1970s harboured creative and political potential, yet also bore internal divisions which mirrored the fragmented postcolonial thinking of the time.

Novelist and activist Tariq Ali delivering a keynote lecture on ‘Solidarity in the 21st Century’, at Axis of Solidarity: Landmarks, Platforms, Futures, Tate Modern, 23–25 February 2019

Photo © Jacob Perlmutter

Vicuña’s call to recognise indigenous knowledge and unspoken histories offered a striking juxtaposition to the strong focus on activism and history-writing in the conference’s two keynotes. In the first keynote, broadly titled ‘Solidarity in the 21st Century’, veteran activist Tariq Ali stressed the loss of post-war consciousness in the present-day generation. Cautioning against being too polite in criticism, Ali’s talk issued several warnings in relation to contemporary discussions in Europe and North America: be cautious of political accounts which present simplified narratives of good versus evil or adhere unquestioningly to ideological positions; be critical of media reports while recognising that young people communicate in different ways; and commit to educating current generations about past struggles.

From a more historical research perspective, the second keynote by the historian Russell Rickford delved into the ways in which African-Americans allied themselves with liberation movements in Angola. Highlighting the complex ideologies behind Angola’s three main political parties which vied for power after the country’s independence in 1974, Rickford’s talk captured how convoluted and, at times, false information circulated across continents under the rubric of solidarity. His call for education and closer attention to the complexities of international affairs paralleled the third artist presentation of the conference. This was given by Ala Younis, who presented her ongoing research into performance art in the Arab world. Younis also explored the wider circumstances and contexts which framed the suicide of Iraq-born artist Ibrahim Zayer in Beirut in 1972, immortalised and misremembered across multiple histories: nationalism in Iraq; political persecution and torture; solidarity with the Palestinian cause; and the dynamics of the contemporary art world.

The ‘Futures of Solidarity Scholarship’ panel with (left to right) moderator Salah M Hassan and Zeyad El Nabolsy, Louis Klee and Brigitta Isabella, at Axis of Solidarity: Landmarks, Platforms, Futures, Tate Modern, 23–25 February 2019

Photo © Jacob Perlmutter

The final panel of the conference, addressing the ‘futures’ of solidarity scholarship, signalled a shift into the present: Louis Klee called for moving away from identitarian readings of the work of indigenous artist-activists such as the Aboriginal poet Lionel Fogerty; and Brigitta Isabella’s emphasis on global migrant workers provided a powerful counter-voice to the mythologised ideals of the 1955 Bandung Conference. Here, on the one hand, solidarities are being actively engaged from bottom-up initiatives by individuals and collectives. On the other hand, the seismic changes brought on by decolonial struggles in the past century are now facing the problems of neo-colonialism.

Taking a more holistic view of the conference’s many layers, messy and unresolved constellations emerged across case studies and chronologies which the three notions of ‘landmarks, ‘platforms’ and ‘futures’ could never fully encompass. These gave rise in the question-and-answer sessions to a number of pertinent questions: what role do ideologies, particularly Marxism, play in the framing of these solidarities? How can we account for nations which have distanced themselves from the idea of solidarity and asserted themselves as neo-colonial forces? We might think of China’s economic expansions in Southeast Asia and Africa; or Indonesia’s exploitation of West Papua. Why are race and class still such dominant frameworks for discussing these histories, whereas discussions on indigenous practices, gender and sexuality, as well as entire regions such as Central Asia and the Pacific, remain absent? While the response sessions gave opportunity to raise these questions, many went unanswered by virtue of further stretching the already expansive scope of the conference.

If we are to set aside these questions as guiding points for future research, there still emerges a more basic question concerning the aim of the conference: was the goal here to produce a new theoretical framework around the workings of solidarity? Looking beyond agendas to further broaden Tate’s international profile, was the conference geared towards producing a new framework for situating and analysing art? If so, how would such a new framing shift away from existing ways of addressing how the arts and culture have challenged the post-war world order? These include notions such as the ‘postcolonial constellation’, defined by Okwui Enwezor as the moment in which the consolidation of the nation state was supplanted by other modes of collective belonging; and ‘worlding’, an idea revisited in this conference by Lydia Liu, which highlights what is at stake when the universal is asserted over local or regional specificities. In light of these pre-existing concepts, the notion of ‘transnationalism’ as an art historical framework remains to be further fleshed out. While the conference yielded several possible ‘artistic’ entry points – the blurred boundary between art and propaganda; ‘translations’ of non-narrative forms; utterances across space and time – political concepts and historical accounts remained the predominant frameworks for this conference. Nevertheless, among the many histories presented there emerged a germinal sense that individual perspectives across discourses of frustration, humanism and network-building offer glimpses into discussions still to come.