In this conversation, Sheba Chhachhi reflects on her trajectory as an ethically engaged artist, as well as the evolution of her practice following the creation of Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91. This interview emerged from several conversations in Chhachhi’s Delhi home beginning in March 2015 and from email exchanges in December 2018 and January 2019.

Sophia Powers: What was your path to discovering photography? Did you aspire to be an artist from an early age?

Sheba Chhachhi: I was dissuaded from pursuing my interest in the arts (which was seen as a hobby) by the faith that middle class families vest in having a degree and earning a living! Following the conventional wisdom of the time I studied economics at Delhi University, and graduated with honours in 1977, only to return to my original desire. By then I had developed a strong interest in what I then thought of as education (later to become communication studies), visual art and theatre.

Before joining the National Institute of Design (NID), I studied and worked at Chitrabani Centre for Social Communication, Kolkata, one of the first media studies centres in India, set up by the distinguished film scholar Fr. Gaston Roberge in association with Satyajit Ray. I was amongst the early graduates of the experimental Diploma in Social Communication, in 1978. The city was our classroom, and each student developed her work through observation, research and discussion and readings with a guide. In my case this was the poet, theatre director and philosopher Deepak Majumdar. Asking him a question was like opening a Pandora’s box of rich associative thinking, replete with cultural and literary references, creative re-imaginings, political anecdotes and folk humour. Through him, Fr. Roberge and other artists/intellectuals who often spoke at or visited Chitrabani, I was exposed to rich and varied thinking and practice in film, photography, theatre, literature and new media, texts which ranged from Marshal McLuhan, John Berger and Gregory Bateson to the songs of the Bauls (a heterodox mystical tradition of Bengal), the psychophysical theatre of Jerzy Grotowski, the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, Ritwick Ghatak, Gene Youngblood’s Expanded Cinema [1970], the list is endless…

Fig.1

Robert Capa

The Falling Soldier 1936, printed later

Gelatin silver print

247 x 340 mm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

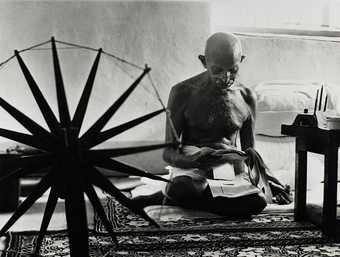

Fig.2

Margaret Bourke-White

Mahatma Gandhi 1946

Gelatin silver print

279.4 x 355.6 mm

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis

Sophia Powers: At what point did ethical concerns become integral to your practice? Was this sensibility something you developed through conversations and training at Chitrabani, or was the impetus primarily from other experiences or convictions beyond your training?

Sheba Chhachhi: The ethics of image making practices, particularly in relation to street photography of the poor and disadvantaged, was an area of emphasis and heated discussion, grounded in an ongoing documentary project by a group of photographers at Chitrabani: why were the powerful often photographed from a low angle? What did it mean when you used a telephoto lens, from a distance, as opposed to shooting with a normal or wide-angle lens, which obliged the photographer to have a human exchange with his subject? What did you choose to include or exclude while framing and why? What were the ethics of Robert Capa’s famous photo of the falling soldier in Spain (fig.1)? Why did Mahatma Gandhi insist that Margaret Bourke-White learn to spin before allowing her to photograph him at the spinning wheel (fig.2)? Although I was not yet a photographer, I joined the group and we sought to develop an ethical code for documentary photographers, perhaps unprecedented, both at the time and later on.

Sophia Powers: Did your experience with Seven Lives and a Dream expand or transform the way you thought about the ethics of image making? If so, what did you learn that surprised you?

Sheba Chhachhi: Much of the conversation about ethics pivoted around photographing the ‘other’. However, even working ethically, with awareness and sensitivity, the power of representation remains with the photographer. After a decade of documentary work, I questioned this in my own work, and in documentary practice in general, which seemed to unconsciously reproduce something close to the colonial recording of ‘natives’. It became necessary to find a path to a representation of ‘citizens’, with agency and control over their own representation. This is what led me to the collaborative staged portraits. I was seeking a possibility of bridging alterity in ways that went beyond my earlier understanding.

Here, first of all, I was working with women that I knew, had known and photographed for a decade; we were sisters in the movement. Secondly, in inviting each woman to choose and co-develop her mise-en-scène, to ‘tell her story’, and perform herself, as well as review and retake till we reached the final images, the asymmetry between the photographer and the photographed was somewhat addressed. Most importantly, for me, we created an intersubjective field: a space of shared subjectivities that was neither hers nor mine but came into being between us, mutually constitutive and unique to that moment and that process. This fundamentally altered my practice.

Sophia Powers: Chitrabani clearly provided a rich conceptual bedrock for your practice. Was it also a place where you began to develop your technical skills, or did that come later on?

Sheba Chhachhi: I had always tinkered with borrowed cameras, but while training in visual communications/graphic design at NID, I started doing darkroom work and was entranced by the magic of the process. I had done a considerable amount of thinking and study on photography, image analysis and photo ethics but it is here that I actually began to use the camera seriously. At NID I was hungry to develop skills – darkroom work, the technical aspects of photography, drawing, typography and graphic design, and also design vocabularies, design thinking and methodologies. Design projects were often tied to social relevance, though also included more market-oriented arenas such as advertising, and I found enough like-minded fellow travellers. The critical and socially oriented framework I had developed at Chitrabani influenced the way I began to photograph, but equally, it came naturally to me to build an empathetic connection with any person that I might photograph.

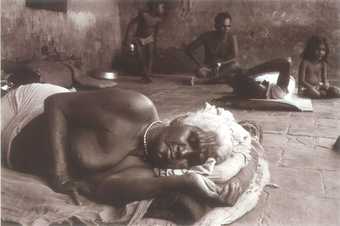

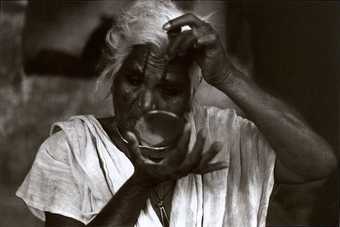

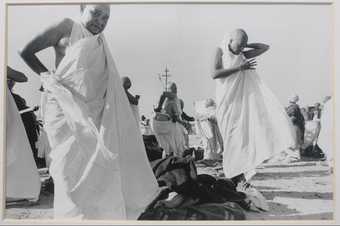

Fig.3

Sheba Chhachhi

Subhadra, Ahmedabad 1979

Black and white photograph

Collection of the artist

© Sheba Chhachhi

Fig.4

Sheba Chhachhi

Subhadra 1979

Black and white photograph

Collection of the artist

© Sheba Chhachhi

Sophia Powers: Who were the first subjects you were drawn to photographing?

Sheba Chhachhi: On my way to the Institute I used to pass by the back veranda of a temple, where many people sat, slept, lived. It was a motley, mutable crowd. I began to notice a half-naked woman who seemed to have established her ‘home’ at one end of the veranda. I was drawn to her unusual way of living, which resonated with earlier encounters I had had with women ascetics in my travels in rural Bengal. One day I stopped and tried to talk to her. She acknowledged my presence, but did not really speak. I began visiting her, carrying, once again, a borrowed camera. I would sit with her, often in silence, watching her, listening to her and finally photographing her. This was Subhadra, the first woman ascetic that I photographed, for my first ever photo-essay in 1979 (figs.3 and 4).

Sophia Powers: I’ve always been intrigued by the figure of Subhadra. Did she ever become interested in the pictures you were taking of her? Was she curious about why you were photographing her, or how the images came out? Do you feel like your relationship with Subhadra developed through the process of taking her picture, or was it something she merely allowed you to do?

Sheba Chhachhi: Subhadra gradually accepted my hanging about and then the presence of the camera. She did not display any curiosity about the photos, but was well aware of the camera. Rather, she continued her way of inhabiting that space without alteration, allowing me to witness and photograph intimate parts of her day. On certain occasions she would talk to me. Here is an excerpt from one such conversation:

One day I came to the river.

As I looked at her tears began to run down my dry cracked cheeks, smarting, hurting.

The water poured out of my eyes and into the river.

I took off my clothes and entered her.

She swelled with my tears, rose, engulfed me.

I was submerged.

Once, twice, three times.

The river was inside me, I was inside her.

Much later I came out, onto the sand where I had left my clothes.

They were gone!

Krishna had stolen them.

I can only cover my body when he gives them back to me.1

Then, one day, as she was counting and sorting out her coins, she made a small pile and gave them to me. Perhaps as recompense for photographing her…

Sophia Powers: Were feminist concerns and women’s activism a part of your life before returning to Delhi from NID? How did you first become involved?

Sheba Chhachhi: My sister, Amrita Chhachhi, co-founded the first feminist group in Delhi, Stree Sangarsh in 1978. Even while I was at NID, I heard from her about the dowry murders, about the horrific violence the group was uncovering. She wrote about their anti-dowry campaign, the street play Om Swaha, and asked me to help make posters. When I came to Delhi in 1980, I was powerfully affected by the struggle against violence against women, the stories of the mothers of dowry victims and the power of the feminists that I met. I became part of it all. I began to photograph our protests and campaigns from within the movement, and for the movement.

Sophia Powers: Do you think that journalistic coverage of those early protests made an impact on the development of your own visual vocabulary?

Sheba Chhachhi: While my early work might have been influenced by the street photography documentary tradition, journalistic coverage had no impact on my visual vocabulary. For me, choosing to come very close, using mostly a normal (50 mm) lens, looking for detail as much as the big picture were instinctive – an instinct honed by critical engagement with photography and representation.

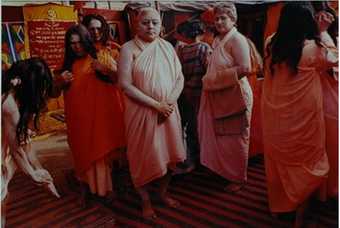

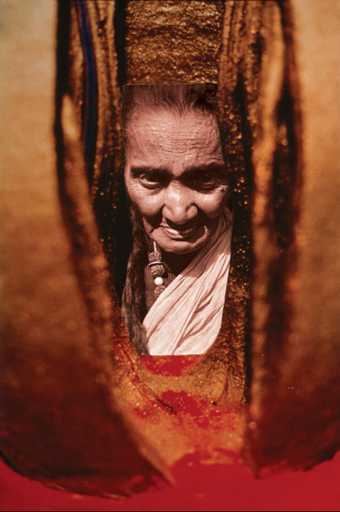

Fig.5

Sheba Chhachhi

Backstage at Sahi Snan Kumbh Mela, Haridwar, 1998 1998

Colour photograph

Poddar Collection, Ranchi

© Sheba Chhachhi

Fig.6

Sheba Chhachhi

Initiation Series 3 2002

Black and white photograph

Poddar Collection, Ranchi

© Sheba Chhachhi

Sophia Powers: I’m curious as to why you decided to shoot in black and white as opposed to colour. I know that you switched to colour for some of the portraits in your 2007 book Women of the Cloth.2 Can you talk about the significance of that shift and how you think about the choice between colour versus black and white in your photographic practice more generally?

Sheba Chhachhi: Black and white offers a degree of abstraction – a step away from simple verisimilitude that I have always preferred to the realism that colour images can produce. The interpretative nature of the image is clearly manifest. However, there are some situations where colour is integral to the subject. In the parallel society which is the world of ascetics and mendicants, dress, accoutrements and ritual markings form a code by which the particular path/sect/religious tradition is read. Colour is critical to this communication. I was interested in these women’s self-presentation and it became essential to work in colour [see fig.5]. On the other hand, the Initiation Chronicle [1998–2002; fig.6], my series that records the ritual performed before women take on the robes of any particular sect, is in black and white. 3

While I remain seduced by the aesthetics of black and white photography, colour is a powerful element in much of my installation and light-box work.

Sophia Powers: Are you still in touch with the women portrayed in Seven Lives and a Dream? How have their lives unfolded since you created their portraits?

Sheba Chhachhi: Sathyarani became the face of the anti-dowry movement. With Shahjahan Apa, she continued to work on violence against women, speaking and campaigning, offering legal aid and counsel to women as well as setting up a shelter. The anti-dowry campaign led to legislation, the establishment of women’s cells in the city, as well as general social stigmatisation of the practice. However, this does not mean that dowry has disappeared even today, though we now have a number of progressive laws. Legal reform, though limited, has been both an area of focus and a gain of the women’s autonomous movement, which is why Sathyarani chose to be staged on the steps of the Supreme Court. She pursued justice for her daughter almost to the very end. Her win in court took thirty-four years, coming just before she passed away in 2014.

I watched with grief as Devi Kripa succumbed to cancer, not long after we collaborated on her portrait. Radha’s work as an academic and writer now focuses on ethnic conflicts and peace processes. Urvashi, co-founder of the first feminist press, Kali for Women, in 1984, continues to be a significant spokeswoman on feminist issues, writing, publishing and creating web-based platforms under the aegis of Zubaan, a feminist publishing house, which she founded in 2003. Shardabehn, indefatigable, continued her work in the community and especially with women panchayats (local councils) till old age and ill health took her from us.

Shahjahan Apa’s eloquent, witty and poetic voice was abruptly silenced by a train accident in 2013. I particularly remember a brilliant speech she made concerning rising religious fundamentalism in 2003. Sectarian violence became a critical issue for all of us in the movement, actually from 1984 on, but especially after the pogrom in 2002 in Gujarat against Muslims. The broader questions of majoritarianism and minority rights, of the rise of minority fundamentalisms, are often pinned around control over women’s bodies, sexuality, mobility and economic freedom, with sexual violence becoming a tool in the hands of those inciting hatred.

Shanti has expanded her consciousness-raising work to build connections with the increasingly rural movement, alongside being an important part of the continuing resistance to violence against women. In the many years that have passed since we made the staged portraits, the women’s movement has seen the emergence of powerful voices such as the Dalit women’s movement, LGBT groups, Muslim women’s organisations – and also had to contend with appropriations of ‘women’s issues’ by Hindu right-wing women-led organisations as well as state institutions, corporations and the market.

The struggle continues, especially as new forms of sexual violence appear, partly because of patriarchal backlash against the emerging independence of women. December 2012 saw many of us back on the streets, after the horrific rape of a young medical student, which led to unprecedented public outrage, huge protests and a new chapter in the resistance against sexual violence. By strange coincidence, this was exactly the time that I revisited the archive of the early protests to create a new installation, Record/Resist.

Sophia Powers: You have described how the early protest images you took were intended as ‘internal documentation’ for the movement. Now they are in the Tate collection! Can you speak about how your thinking regarding the audience and context for viewing Seven Lives and a Dream has evolved over the years?

Sheba Chhachhi: My practice is dialogic, both in its making and in my engagement with modes of reception. I seek to open a conversation with the viewer and many of my formal experiments are informed by this interest. In the early years, the protest images were circulated and shown primarily within the women’s movement in India, South Asia and internationally. Not published in mainstream newspapers or magazines, but rather in small runs of low-cost books or pamphlets, hung by clothes pins on laundry lines in shanty towns and community centres. They were shown at the annual women’s conferences, turned into postcards to raise funds for a crisis centre, and even made into a small tabletop accordion-type fold out exhibition which was carried whenever any one of us travelled to share the struggle.

In 1988, a friend and fellow feminist photographer based in the UK, Mumtaz Karimjee, invited me to participate in a gallery show, Four Women Photographers at Spectrum Photography Festival in London. I had never imagined these protest images in a gallery – this was a world far removed from the activist or academic contexts I was familiar with. I was sceptical, uneasy, even uncomfortable but chose to go ahead and see what this might mean. A number of talks and group discussions were part of the show, and it was in these conversations that some of my reservations dissolved. Such images of Indian women – struggling, militant, seeking justice, had just not been seen! Particularly for young British Asian women, these were women who looked like their own mothers and grandmothers, but were radically challenging structures of family and state. Another space for interaction with the images had emerged.

By 1990 I was developing the collaborative staged portraits, which, juxtaposed with selections from the protest images, make up Seven Lives and a Dream. These portraits marked a shift in my practice away from the documentary, towards art, and were presented in non-profit cultural spaces and galleries as well as at movement events, reaching out to wider audiences. One interesting context was as part of a theatrical production, My Story directed by Rustom Bharucha in 1992, based on a book by Flavia Agnes, a feminist activist from Mumbai, where the photos were integrated into the performance as well as displayed in the foyer.

Fig.7

Sheba Chhachhi

Detail of Wild Mothers I: The Wound is The Eye 1993

3 terracotta sculptures, 9 terracotta tablets, hand-tinted silver gelatin prints, found images, turmeric, pigment and sand

3500 x 2100 x 2500 mm

Collection of the artist

© Sheba Chhachhi

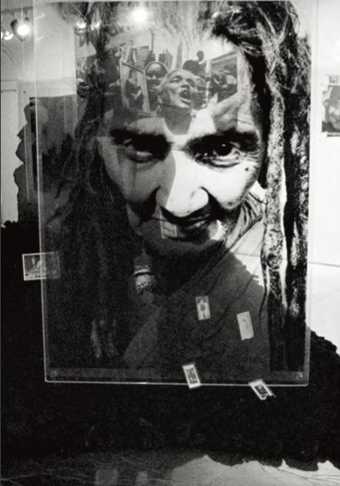

Fig.8

Sheba Chhachhi

Wild Mothers II: The Mirror is the Witness 1994

21 black and white film positives, terracotta sculpture, stone fragments with text, coal, found images and reflective polyester film

1500 x 900 x 3500 mm

Collection of the artist

© Sheba Chhachhi

Image courtesy the artist

The conversation now also encompassed questions about representation, agency and self-narration. I moved on to creating large photo-based installations; bringing photographs of women ascetics and feminist activists together in space with sculptural elements, text and reproduced historical archival material in a series called Wild Mothers (fig.7). On one hand, I was troubled by the commodified consumption of photographs, whether in media or art spaces. On the other, relocating the photograph as an object within sculptural space offered the possibility of reconfiguring the habit-ridden encounter with a photographic image. I wished to reinvest the viewing of photographs with time. Wild Mothers II: The Mirror is the Witness 1994 (fig.8) included images from this series and became a rich site for discussions, both organised and informal. After years of taking work out into the community, I began to bring women from the communities, activists and friends from the movement into the gallery space. In Wild Mothers II, a reflective film on the floor acted as a mirror, the viewer seeing herself inside the installation, part of the legacy of powerful women represented there. Further, as the viewer moved around the space, she saw a different set of overlays, new juxtapositions of the same images. This early experiment in what I think of as embodied viewing, where the artwork engages not just the eyes or ears of the viewer/participant, but her entire body, has developed into the immersive sensorial experiences that I now create.

Fig.9

Sheba Chhachhi

Installation view of Record/Resist 2012 at the 9th Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, 2012

Photo-video installation, 21 black and white digital archival prints and 17 min video loop

Collection of the artist

© Sheba Chhachhi

Record/Resist, a photo-video installation which revisits the archive of the women’s movement in 2012, seeks to create an encounter with the photos which shifts between the intimacy of meeting an individual image and the strength of many women coming together in struggle through the composite, by inviting the viewer to walk into and through the photographs (fig.9). This was created first for the Gwangju Biennale, but has since been shown in museums in India and elsewhere. These public sites, like Tate, are an institutionalised form of the public domain that this work has always occupied, bringing new variations in the kinds of viewers, and viewing experiences.

Sophia Powers: I know that your recent work has become increasingly engaged with the ecological plight of our environment. Writers like Radha Kumar have made the historical connection between the women’s movement and environmental concerns in India – in part because degradation of natural resources disproportionately affects the sort of labour women do to support their families. Do you regard your turn towards environmentally focused art as reflecting a gendered ethics of ecology, or are you more focused on the universality of the issues at hand?

Sheba Chhachhi: I have been thinking about and working on questions of urban ecology for over a decade now. This is feminist work. Not only because women bear a disproportionate burden of ecological degradation, but because the crisis itself is produced by a patriarchal paradigm. Eco-feminism articulates the deep structural connection between the domination of and extraction from the earth and the subjugation of women. I believe that feminism is not only about women, but is a political philosophy which analyses the power relationships that construct our world, therefore it addresses ‘universal’ issues.

In fact, much of my work has been concerned with recuperating premodern knowledge systems. I believe that these prior epistemologies hold kernels of eco-philosophy, of ways of inhabiting the earth which can help heal the rupture between humans and the rest of the natural world.