Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91 emerged out of Sheba Chhachhi’s prolonged and multi-faceted engagement with anti-dowry protests in Delhi, which themselves arose from the broader women’s movement surging across India in the late 1970s and early 1980s. This essay grounds Chhachhi’s practice in Indian feminist activism and its visual representation over this period, focusing particularly on the anti-dowry movement and its relationship to the simultaneous anti-rape agitations with which Chhachhi was also involved. Both of these movements included a range of activities such as demonstrations, sit-ins and street plays that were aimed at a broad swathe of society. Legal progress was achieved in response to both issues; however, the women’s movement as a whole was also complicated by fraught disagreements over issues of representation across caste and class divides.

I argue that the nineteen images that make up Chhachhi’s Seven Lives and a Dream (hereafter Seven Lives) express an evolving investment in both the psychological and the socio-cultural complexity and specificity of her photographic subjects. This distinguishes her practice from prevailing mainstream journalistic coverage of the women’s movement. Such focus is extended and intensified in the collaborative strategy at the heart of the eleven staged portraits in the series, in which women from diverse backgrounds worked with Chhachhi to portray themselves as they wished to be seen. Taken together, the nineteen photographs in Seven Lives both present and perform a larger truth about the heterogeneity of the women’s movement and the possibility for representational diversity.

Mathura and the movement’s roots

What has often been called the ‘contemporary’ feminist movement in India began with a powerful wave of activism in the late 1970s that focused on issues of sexual violence against women.1 The catalyst for this new wave of activism was outrage over the rape of a teenage woman from a tribal minority named Mathura. She had fallen in love with a young man from her village and her brother did not approve. In order to obstruct their relationship, he brought his sister to the police station on the evening of 26 March 1972, claiming that her lover’s family was attempting to abduct her.2 Following a routine investigation, however, Mathura was asked to stay behind and was raped by two intoxicated policemen. Boldly defying convention, Mathura and her family decided to press charges against the officers, but when the case came to court two years later, the two men were acquitted on the grounds that the judge determined Mathura had not been visibly harmed and was already sexually experienced, and thus must have entreated the men to penetrate her on account of her loose moral character.3 Two years after the acquittal, the Bombay High Court overturned the judgment and the policemen were sentenced to jail, but two more years after that, in 1978, the Indian Supreme Court overthrew their convictions and the men were declared innocent.

Over the long and tumultuous trajectory of this case it gained nationwide attention, and many were shocked at this final verdict. The judgment incited a powerful backlash that would prove to be a turning point in the women’s activist movement. Several prominent lawyers including the dean of the University of Delhi law school petitioned to reopen the case and amend the country’s laws regarding rape. Grassroots women’s groups formed across the country in response to the ruling and organised a handful of highly visible protests in public spaces. These combined pressures resulted in substantial legal change. The law regarding rape in India was amended in 1983 to conceal the identity of the victims, recognise the category of ‘custodial rape’ (rape perpetrated by those in institutional positions of power) and shift the burden of proof from the accuser to the accused.

It is worth noting that members of the women’s movement were divided over several of these amendments.4 Concealing the victim’s identity was perceived as potentially problematic because it restricted the public’s ability to monitor the trials. Shifting the burden of proof to the accused was even more controversial due to concerns that this contradicted the principle that a suspect was innocent until proven guilty. Furthermore, some activists were concerned that political opponents might take advantage of the clause to frame male activists. Despite these apprehensions, however, the amendments were largely hailed as a victory for the women’s movement.

Fig.1

Women protesting against rape, New Delhi, 8 March 1980

Black and white photograph

© Getty Images

While anti-rape activism was among the first issues to unite women across class lines,5 there was still a significant imbalance in the realm of representation – a concern that was highlighted by the movement’s tendency to overlook the perspectives and desires of victims themselves. This became especially evident in the case of Mathura. A major wave of protest was organised across the country on 8 March 1980 to reopen the Mathura rape case (fig.1). However, it was long after these efforts were underway that the primarily urban, educated leaders of the movement thought to contact the victim, whose rural, working class circumstances had so few parallels to their own. What did Mathura herself feel about these efforts? Was she in favour of nationwide mobilisation to draw attention to an assault that had traumatised her eight years earlier? These questions were especially urgent considering that her identity was public, and the societal shame associated with rape victims was often life-shattering. By this point, Mathura was married and had moved to a different village.6 When members of a Bombay-based activist group managed to locate her, she was surprised to learn the scope of the movement that her case had inspired across the country. She supported the activists’ efforts, but harboured little hope that their actions would effect significant change.7 Leaders of the movement were relieved that Mathura did not resist their rallying around her cause, but were also troubled that consulting the victim at the centre of their agitation had been little more than an afterthought.8

Growth and division

These concerns were part of a much larger set of issues regarding class and caste that faced the contemporary women’s movement as it evolved in the late 1970s and 1980s. In particular, some activists were concerned that the gulf separating the experience of middle class women and working class women was too large to be bridged responsibly. How could urban, middle class activists agitate on behalf of their working class sisters whose life circumstances were so vastly different from their own? Indeed, given the fact that women’s oppression was so closely tied to economic oppression, some activists wondered if it even made sense to organise women along gender lines alone. Perhaps a better solution would be to bring men and women together to agitate against specific economic, social or environmental issues that adversely affected the lives of women.9 The related but separate issue of caste within the movement was similarly troubling to many activists, who were concerned that the elite, high-caste leadership of feminist groups would necessarily lead to the marginalisation of dalit (low-caste) voices and the minimisation of experiential difference across class lines.10 Finally, many activists were concerned that the very basis of feminism was not only elitist, but imperialist, due to the Western intellectual lineage to which it was often ascribed.11

The women’s movement must, of course, be understood as a diverse range of groups, each motivated by varying aims and allegiances.12 The broadest distinction, however, has often been made in terms of so-called ‘autonomous’ organisations as distinct from groups with specific political ties, such as the two Delhi-based groups Janwadi Mahila Samiti (aligned with the Communist Party of India (Marxist)) and Mahila Dakshta Smiti (associated with the Janata Party).13 As feminist concerns gained momentum, other modes of organisation emerged as well, such as grassroots centres offering services to vulnerable women and academic institutions promoting the emergence of women’s studies as a formalised field at university level.14 While members of all such groups sometimes came together to protest specific issues such as dowry-related violence and rape, Chhachhi’s own investment lay in documenting the activity of autonomous groups like as Stree Sangarsh, of which her sister was a founding member. As Chhachhi explained:

The first autonomous feminist groups came out of left student politics and were socialist feminists, so a concern with class was central. However, we did not accept that it was the only basis of inequality, as gender cuts across class, with upper class women being subject to patriarchal violence as much as those of other classes, albeit with important differences. This was the ideological basis – class, gender and caste.15

Some scholars have pointed out that many of these autonomous groups were largely composed of educated, middle class women (such as Chhachhi and her sister).16 Yet there was a strong commitment to eschewing hierarchical structures of leadership, and such groups made a major effort to include members from across the class spectrum, as Chhachhi’s photographs attest.17

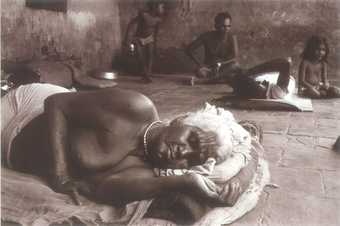

Fig.2

Sheba Chhachhi

Subhadra, Ahmedabad 1979

Black and white photograph

© Sheba Chhachhi

Chhachhi returned to her hometown of Delhi in 1980, just as the anti-rape protests were increasingly unfolding in the public eye. She had just completed a degree at the prestigious National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, where she had already begun to develop an interest in what she would later call ‘indigenous feminism’, or pre-modern, indigenous forms of feminism originating from the Indian subcontinent.18 Specifically, Chhachhi had begun to take photographs of Subhadra, a female Hindu ascetic or renunciate whom she had befriended (fig.2). Subhadra’s life represented a powerful alternative to the established trajectory of an Indian domestic woman’s life. Ascetics such as Subhadra renounced all family ties and assumed wholly new and independent itinerant identities in service of their faith. In some senses, the sadhu tradition of renunciation and the women’s protest movement represent opposite reactions to the power of Indian patriarchy insofar as ascetics sought to escape patriarchy by opting out of the social system altogether, while the protesters sought to alter the system itself. However, Chhachhi’s attraction to both modes of resistance demonstrate her sensitivity to the diversity and individuality of Indian women’s struggle for autonomy.

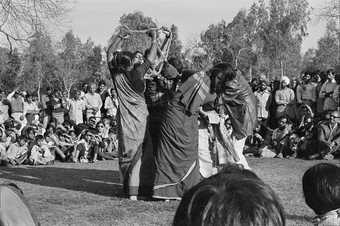

Fig.3

Sheba Chhachhi

Street Play on Amendments to the Rape Bill, Karol Bagh, Delhi, 1980 1980

Black and white photograph

Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong

© Sheba Chhachhi

Because Chhachhi’s sister Amrita was a founding member of Stree Sangarsh, it was natural for the photographer to become quickly involved in the movement. Her newly honed skills as a visual artist were quickly put to use designing posters and pamphlets for the protests, and she began to take photographs to document the wide range of the group’s activities.19 Besides the well-publicised marches, the women organised public testimonies, sit-ins, and even dramatic performances on the street. Many of Chhachhi’s photographs from this period foreground the magnitude and intensity of the crowd. One particularly dynamic image shows a play about rape being performed in a grassy clearing to a large audience of (mostly male) onlookers (fig.3). The bodies of five or six actors are frozen in an instant of apparent frenzy. Although their activity is hard to interpret definitively, a group of women hold a thick rope above their heads with which they appear to have entrapped a mustachioed man between them. Neither the action nor the actors are pictured with precision, but the drama of the instant is unequivocal. Chhachhi’s image – intended for internal circulation rather than broader press coverage – did much to demonstrate how powerfully the performance captured the attention of the crowd.

Tarvinder Kaur and anti-dowry activism

Outrage over gender-based violence was intensified in 1979 by what became another infamous case – the murder of twenty-four-year-old Tarvinder Kaur by her in-laws, who were seeking greater dowry from her family. The issue of dowry has an extremely fraught and complex history in India. The term ‘dowry’ refers to a price in goods, cash or both that a bride’s family is asked or expected to pay to the husband’s family on the occasion of the daughter’s wedding. This practice stretches back to antiquity and was (problematically) rationalised as a way to offset the financial burden that the wife’s maintenance would impose on the husband’s family over the course of her life. Dowry has been illegal in India since 1961, however this prohibition was largely ignored and requests for dowry continued unchecked in many communities across India. In some cases, the husband’s family would press the wife’s family for further dowry after the wedding, exhorting pressure through physical and psychological harassment of the new bride. The growing prevalence of this practice was tied to the accelerated consumerism of the time.20 Families would often refuse to take back their mistreated daughters due to a fear of stigma surrounding the altercation, which might decrease their other children’s chances of receiving attractive marriage proposals. Hence, many young women felt they had no choice but to remain in potentially life-threatening situations.

In Kaur’s case, her groom’s family had repeatedly requested funds for the expansion of their spare parts business. When Kaur’s family refused, her mother-in-law and sister-in-law doused Kaur with kerosene and set her on fire. She survived just long enough to describe the incident on her deathbed. The police ignored her declaration, however, and registered the case as a suicide. Indeed, it was exceedingly common at the time for police officers to ignore even the most blatant evidence of dowry-related murder, either because they were bribed by the family or because they simply did not want to get involved in what was largely considered to be a ‘family matter’.21

Tarvinder Kaur’s relatives certainly agreed that her death was a family matter – theirs – and one for which they were ready to fight. Her family’s protest caught the attention of the Indraprastha College Women’s Committee, who immediately spread the news to student groups and women’s organisations such as Stree Sangarsh and Nari Raksha Samiti. These groups quickly arranged major public protests that drew widespread attention across Delhi. Not only were the marches organised along major public routes at the city centre, they also snaked through Kaur’s in-laws’ own neighborhood, drawing direct attention to the perpetrators. The crowd surged as more and more people joined in from the street. As the feminist publication Manushi described it: ‘There were working women, housewives with babies in arms, some burka-clad women and washerwomen from as far away as Manjnu ka Tila. A man came all the way from Punjab to voice his protest.’22 Such swelling ranks drew major coverage from the national press.

Kaur’s death was not the only murder protested by the crowd – dowry-related deaths, often passed off as kitchen accidents, were common across the country despite rarely being reported as murders. Such violence was most prevalent in North India, and official statistics cited 112 dowry deaths in Delhi between 1982 and 1984.23 Yet the anti-dowry cell of the Delhi police reported that 610 New Delhi brides had died by burning in 1982 alone, and the number appeared to be growing each year.24 Relatives of the deceased were often among the most dedicated demonstrators in such cases, and two of the protagonists of Seven Lives lost their daughters to dowry-related murder.

Fig.4

Sheba Chhachhi

Shahjahan Apa – Anti Dowry Public Testimonies, India Gate, Delhi 1986, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

381 x 568 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

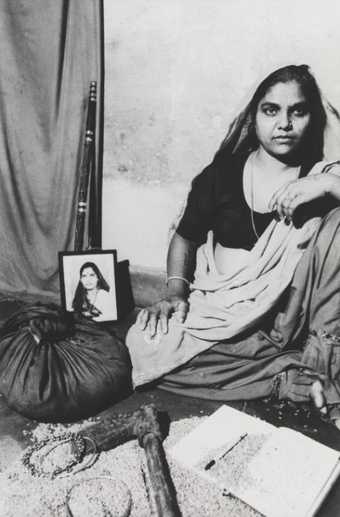

Fig.5

Sheba Chhachhi

Sathyarani – Anti Dowry Demonstration, Delhi 1980, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

386 x 567 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Chhachhi’s protest images in Seven Lives register the anguish of both of these activists as they hold up photographs of their lost children. Shahjahan Apa shows an image of her eldest daughter Noorjahan (fig.4) and Sathyarani shows her pregnant daughter Shashi Bala (fig.5), both of whom were burned to death in 1979, much like Tarvinder Kaur. Together, these women set up a shelter and legal aid centre known as Shakti Shalini for women suffering from violence within the family, and they devoted their lives to activism around women’s rights. In Chhachhi’s photographs, however, the focus is trained on the women themselves and the images of their daughters, emphasising the very personal grief and tenacity that shaped their identity as prominent figures in the movement.

Challenging journalistic iconography

This comparatively intimate focus sets Chhachhi’s images apart from prevailing journalistic paradigms of the time. Consider her portrait of Sathyarani (fig.5) compared with the iconic press photograph taken of the anti-rape protests in 1980 (fig.1). The earlier photograph shows just one of the protests organised on International Women’s Day that drew thousands of women onto the streets across the cities of Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad and Nagpur.25 Like Chhachhi’s image of Sathyarani, the focal point of the photograph is a woman activist with her arm raised. Beyond this trope, however, the similarities dwindle. Chhachhi’s picture emphasises the emotion in Sathyarani’s face, whereas the Mathura rape demonstration photograph presents the woman with her arm raised as just one figure among many, her individuality obscured by the iconicity of her gesture. In the case of Chhachhi’s image, we don’t even see Sathyarani’s arm fully extended, so tightly is the image focused on her visage in order to emphasise her affective dynamism. The earlier photograph is also distinguished by the clarity of its physical setting. The courthouse is clearly identifiable in the background, framing the crowd of women against a bastion of centralised (and historicised) authority. Chhachhi’s image also captures a building in the corner, but it is barely discernable, representing instead an anonymous non-place of urbanity.

The most striking contrast between the two images, however, lies in the diverging depictions of the signage the women hold up to express the content of their grievances. The earlier picture is dense with protest posters that are both highly legible and remarkably uniform. In fact, two out of the three slogans written in English are repeated – two visible signs read: ‘REOPEN THE MATHURA CASE’, while three read: ‘RAPE IS A CRIME AGAINST CIVILISATION’. The consistency of these sentiments is underscored by the fact that all of the visible English-language signs appear to be written by the same person, judging by the consistency of their blocky, idiosyncratic font. In Chhachhi’s picture, by contrast, neither the two Hindi nor single English signs are legible, owing to the photographer’s more tightly focused composition. Instead, the viewer’s eye is drawn to the photograph of Sathyarani’s murdered daughter, taken on her graduation day. Sathyarani holds this image up as an index of the tragedy she protests. The photograph offers a poignantly private alternative to the generalised slogans articulated by the women protesting to overturn the Mathura rape case. Through highlighting the psychological intensity of a single protester and emphasising Sathyarani’s connection with her daughter, a unique victim, Chhachhi’s image offers a distinctly individualised picture of a mass movement that sets it apart from the highly circulated photograph of the crowd mobilised by Mathura’s rape.

Fig.6

Sheba Chhachhi

Urvashi – Street Play, ‘Om Swaha’, Mehrauli, Delhi 1982, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

569 x 380 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

This focus extends across the protest images included in Seven Lives, such as Urvashi – Street Play, ‘Om Swaha’, Mehrauli, Delhi (fig.6), taken in 1982. This image documents the performance of a street play that dramatised the dowry-related abuse of a young bride at the hands of her in-laws. It focuses on the body of a single woman with an anguished expression, straining against a band of cloth. There were two endings presented at the play’s conclusion. In the first, the girl is killed. In the second, she escapes the situation, pursues an education, and stands up for the rights of women like herself.26

The play’s concept was developed through conversations with a group of women who had been directly affected by dowry-based violence, and the story was modelled after a specific incident as described by the victim’s parents. Thus, like Chhachhi’s photographs, this creative process was fundamentally collaborative across class lines. The format of the play was also specifically conceived to communicate with women who may be illiterate and might have less access to feminist activist circles. Street theatre of all kinds was a popular and easily legible form of entertainment for the working class. Because dowry deaths were especially prevalent in Punjabi communities, the format of the play was adopted from Punjabi folk theatre so that it would be easily understood by audiences across North India.27 Professional theatre practitioners Maya Rao and Anuradha Kapur, the latter a recent PhD graduate from the theatre studies programme at Leeds University in the UK, scripted and directed the production together, bringing on board dozens of volunteer actors as the play travelled across Delhi.28

Because the strength of the anti-dowry movement was so widely felt, legal change came relatively swiftly, although it was far from satisfactory in the minds of many activists.29 Within a year of the 1979 protests, the government passed a law that required a mandatory police investigation of any death of a woman less than five years into marriage.30 Other amendments followed, such as broader recognition of cruelty to women, provisions for individuals to lodge complaints, and stricter sentencing. While activists celebrated these victories, the inconsistent application of these amendments demonstrated the limitations of a purely legal resolution to the immensely complex and socio-culturally engrained challenges facing Indian women. In the early years of the 1980s, activists began to subtly shift their tactics.31 Along with mass agitation aimed at influencing government policy, feminists began to devote greater effort to building their own networks, support groups and centres for vulnerable women. There was also an increased focus on following up on the cases of individual women as they navigated year upon year of complex litigation. Chhachhi’s work echoes this growing emphasis on the individual and their shifting circumstances and attitudes over time.

Performing subjectivity

Chhachhi’s increasing investment in the complex subjectivity of the activists with whom she worked was profoundly extended in her staged portraits in Seven Lives. Fuelled by her mounting skepticism regarding the documentary genre as well as her concern that her images did not capture the full complexity of her subjects, Chhachhi approached eight of the women she had photographed over the course of the anti-dowry protests and proposed that they work together on a series of staged portraits that would allow them to present themselves as they pleased. Of the eight collaborations that Chhachhi initiated, seven were taken forward. They took place over several months and spanned each phase of the images’ production, from conception and staging to selection and printing.

The broad range of class backgrounds that the women represent is striking, and is made evident by their dress and home environments. Chhachhi reported that she worked with three middle class women and four working class women, and had substantially different experiences creating the portraits with each. Perhaps surprisingly, she found it more difficult to collaborate with the middle class women whose backgrounds were more similar to her own. This was largely due to different levels of comfort with self-performance, on the one hand, and different expectations regarding the nature of photographic representation on the other. As Chhachhi explained:

Middle-class women had much more difficulty with accepting the performative invitation. To perform oneself was something that the working-class women understood immediately and responded to. It’s also part of the vernacular vocabulary of photography – to go into a studio where you perform a character or pose against a painted backdrop … The portrait that failed was of a close friend, an older woman, middle class … she wanted to be revealed, somehow, through the camera, and she expected my intimate knowledge of her to sort of manifest without her having to perform. She was very reluctant to perform. For her, that would become false or fake. It was as if she was imbued with some of the western canon, as a subject, and with that tradition of portraiture where your essence is captured, almost unknown to yourself. So it was curious – we worked and worked, kept re-photographing, and it just never came together. It was very interesting.32

Thus, Chhachhi’s interest in performance was something that her working class subjects intuitively understood as integral to the photographic medium, taking this up more easily than her middle class subjects.

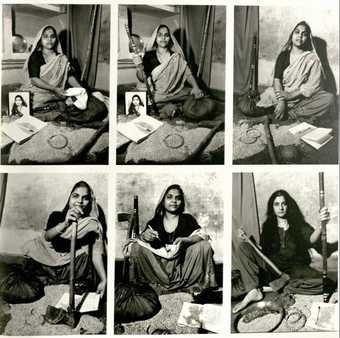

Fig.7

Sheba Chhachhi

Sathyarani – Staged Portrait, Punjabi Bagh Residence, Delhi 1990, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

382 x 568 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Fig.8

Sheba Chhachhi

Sathyarani – Staged Portrait, Supreme Court, Delhi 1990, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

772 x 516 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

One of the initial choices each woman made about her portrait was where it would be set, and what props should be selected for inclusion. Some women chose a public space while others preferred the domestic sphere. Sathyarani chose both, staging one image in her Punjabi Bagh residence and the other on the steps of the Supreme Court building, where her daughter’s wedding sari snakes its way down the stairs through files from her protracted legal case (figs.7 and 8). Indeed, both images include reams of legal documents as well as the photograph from her daughter’s graduation day – the same one Sathyarani held up at rallies over a decade earlier (see fig.5). The continuity between the three images is striking, suggesting that her daughter’s case had become the central focus of her life across both time and space, bridging years as well as the divide between public and private subjectivity.

Fig.9

Sheba Chhachhi

Shahjahan Apa – Staged Portrait, Nangloi, Delhi 1991, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

785 x 521 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Fig.10

Sheba Chhachhi

Shahjahan Apa – Staged Portrait Set-Up, Nangloi, Delhi 1991, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

783 x 520 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Shahjahan Apa selected her own one-room home as the setting for her portrait (fig.9). For Shahjahan, the home was intimately intertwined with memories of her murdered daughter and her subsequent engagement with activism. As she described years later to Urvashi Butalia (the same Urvashi featured in Seven Lives), ‘Even I don’t know what attachment I have to this place. I started my work from here and my daughter died here; I started my life from here and this is the reason why I don’t feel like leaving Nangloi.’33 Chhachhi’s portrait combines images of Shahjahan’s years of activism with more idiosyncratic domestic details such as a sewing machine, shelves full of cups, and even a small model house made of tinsel. The sewing machine is a particularly poignant emblem of Shahjahan’s past, as she escaped her abusive husband and village life by coming to Delhi to support herself and her nine children on the basis of her sewing skills. Her sister-in-law lent her the first machine she used. The machine that she was later able to buy for herself with her savings – presumably the machine pictured – represents not only independence from patriarchal abuse, but also an emblem of women’s life-saving generosity to one another. The significance of these domestic items is highlighted by a second photograph that shows the same scene with Shahjahan missing – replaced on the bed with her own photograph and a cloth bag (fig.10). Thus, the material circumstances of each woman’s life were clearly fundamental to how they wished to be comprehended.

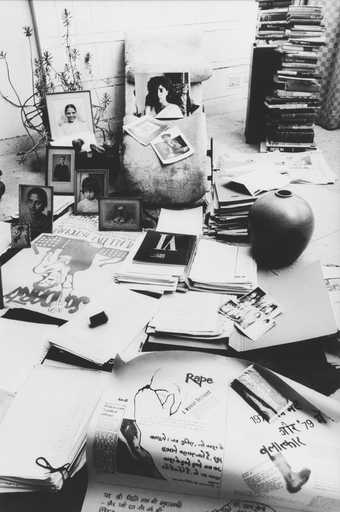

Fig.11

Sheba Chhachhi

Radha – Staged Portrait Set-Up, Anandlok, Delhi 1991, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

771 x 517 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

The series includes another portrait bereft of a sitter – Radha’s ‘staged portrait set-up’ – but one that suggests a very different material experience of life to that of Shahjahan (fig.11). In Radha’s image, books, pamphlets and photographs cascade across the floor. Much of this material demonstrates leftist affiliations, such as a Solidarność Polish solidarity poster, or had been made specifically in service of the Indian women’s movement, but the photographs in the background suggest friends and relatives from an earlier era. The composition is accented by an elegant ceramic vase set between scattered pages. The mise-en-scène suggests Radha’s refined existence revolving around the written word, as opposed to the relatively working class connotations of Shahjahan’s room.

Fig.12

Sheba Chhachhi

Radha – Staged Portrait, Anandlok, Delhi 1991, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

790 x 517 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

The impression of Radha’s rarified milieu is accentuated by the portrait in which she is present, which shows her reclining languidly next to two teetering towers of books (fig.12). Her hair is fashionably coiffed and distinctly shorter than the longer, traditional style shared by the other women in the series. Three photographs are propped up in their frames at her feet, showing her father, a senior bureaucrat in an elegant Western suit; her mother, an eminent historian; and Radha as a child. The riot-gear footwear poking subtly from beneath her sari is the only definite index of activism in a portrait that otherwise suggests elite education and aristocratic panache.

Fig.13

Sheba Chhachhi

Shanti – Staged Portrait, Dakshinpuri, Delhi 1991, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

777 x 517 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Fig.14

Sheba Chhachhi

Shanti – With Children, Dakshinpuri, Delhi 1989, printed 2014, from Seven Lives and a Dream 1980–91

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

778 x 528 mm

Tate

© Sheba Chhachhi

Shanti’s portraits, by contrast, do not aspire to glamour. The first presents a woman of humble circumstances who gazes with such resolute intensity that one feels the whole world may be under her command (fig.13). She is wearing traditional clothing from her home state of Rajasthan, which she left as a migrant labourer with her husband many years before. Her journey is signalled by a cloth bundle in the foreground resembling that which she would have used to transport her belongings, placed beside an axe and scattered grain, which together suggest her agrarian background. Shanti also includes a photograph of herself wearing a bindi, taken before her husband passed away in an accident. A second photograph of Shanti stands out among the staged portraits for its inclusion of the subject’s family members – in this case, three of Shanti’s young children (fig.14). Shanti lies on the floor cuddled between the two younger ones, apparently lost in thought, while her oldest daughter sits upright against the wall, confronting the viewer with a gaze that recalls her mother’s own singular intensity. This image suggests a self that is inherently intimate and essentially relational, in that it expands the realm of associations viewers may bring to bear on activists like Shanti. Their portraits are not merely stoic, tragic or resolved. There is also room for joy and familial fulfilment in such lives.

Fig.15

Sheba Chhachhi

Excerpted sequence from the process of making Shanti, Staged Portrait, Dakshinpuri, Delhi 1989

Published in Kumkum Sangari (ed.), Arc Silt Dive: The Works of Sheba Chhachhi, New Delhi 2016, p.167

© Sheba Chhachhi

The intersubjective sensibility that Shanti expresses in her family portrait is echoed in another image that came out of her collaboration with Chhachhi – one that was not included in the Seven Lives series, but that nonetheless offers a powerful insight into the project’s progression. It is a photograph of Chhachhi herself that was published in the 2016 monograph on her practice, Arc Silt Dive (fig.15).34 The photographer poses among the grain, the notebook and the axe within the staged setting that Shanti had orchestrated for her own portrait. As Chhachhi later described: ‘She put me in her theatre, and photographed me. Because we were working on the tripod, she said show me how it works and go sit there, and do this and you do that. That’s right!’35 Chhachhi is shown barefoot with a staff in her left hand and the axe in her right, almost like the mythical objects gripped by a deity. She gazes out at the viewer with the same steely intensity as Shanti, as if inhabiting her space has allowed Chhachhi to transmit Shanti’s spirit.

The fact that Shanti asked Chhachhi to step into her portrait expresses the depth of solidarity she felt with the photographer. The invitation suggests that Shanti did not feel that the two women were so different that the photographer could not assume the space she had created for herself. Nor was the gesture an attempt to merely elide the social differences between them. This was not an exercise in finding common cultural ground. Rather, Shanti had worked to articulate a visual representation of her own unique identity, inextricably tied to socio-cultural circumstances that were distinct from Chhachhi’s, and then asked the photographer to explore her own self-expression within this frame. Thus, Shanti’s image might be seen as a reversal of the paradigmatic politics of representation with which the women’s movement struggled throughout its evolution.

A heterogeneous unity

Seven Lives and a Dream represents a complex reflection on, as well as a response to, the issue of class divisions that troubled the women’s movement in India throughout its history. While Chhachhi was involved in documenting many issues within the broader women’s movement, such as agitation against rape and sati (the self-immolation of a bride following her husband’s death), her photographs of the anti-dowry protests show the strongest commitment to capturing the unique and complex subjectivity of individual activists. Rather than focusing on the dynamism of the crowd, images like Sathyarani – Anti Dowry Demonstration, Delhi (fig.5) draw the viewer into the experience of a single woman. It is not the power of the masses that Chhachhi emphasises, but the psychological force of the movement’s protagonists. This sets these images apart from contemporary press coverage as exemplified by the infamous Mathura rape protest photograph discussed earlier (fig.1). These qualities even represent a transformation of Chhachhi’s own artistic focus, as might be seen in a brief comparison of her two street-play shots discussed earlier: while one offers a wide-angle perspective on a group of actors entrancing a large audience (fig.3), the other, an image of Om Swaha taken just two years later, trains our view on the anguish experienced by a single woman (fig.6).

This careful attention to the individuality of the movement’s protagonists also conveys the social heterogeneity at the heart of the women’s movement. Chhachhi’s investment in her subjects’ psychological as well as socio-cultural specificity was powerfully extended through the staged portraits in Seven Lives, which allowed for a mode of self-performance that was especially comfortable for her working class subjects. Such collaborative representations negated a perception of elitism as endemic to the movement that has long troubled activists. Many have asked: how can women from diverse classes unite for a single cause? How could working class women share equal footing with middle class women in such united fronts? While these were deep and valid concerns, at times they also had a paralysing effect on the women’s movement. As Radha Kumar articulated, these anxieties have resulted in:

A kind of objectification of both working-class and middle-class women, for the self-awareness which generally facilitates intimacy was invalidated. Emotional needs or desires were thus relegated to the personal or individual sphere, and the sort of public-private dichotomy which feminists opposed in their campaigns against rape or violence in the family, appeared in a different form within their own groups.36

Chhachhi’s images offer a compelling visual response to these concerns. She challenges this view by pointing out how her collaborations were indeed grounded in extended relationships of trust across class lines, remarking that ‘I would not have been able to make the staged portraits if I did not already have intimate relationships with the women I collaborated with!’37 Indeed, Seven Lives suggests a vision of the movement that is fundamentally heterogeneous in its unity, and intimate in its appeal.