17 rooms in Historic and Early Modern British Art

Artists in Britain turn away from Victorian values, finding inspiration in individual experience and ‘art for art’s sake’

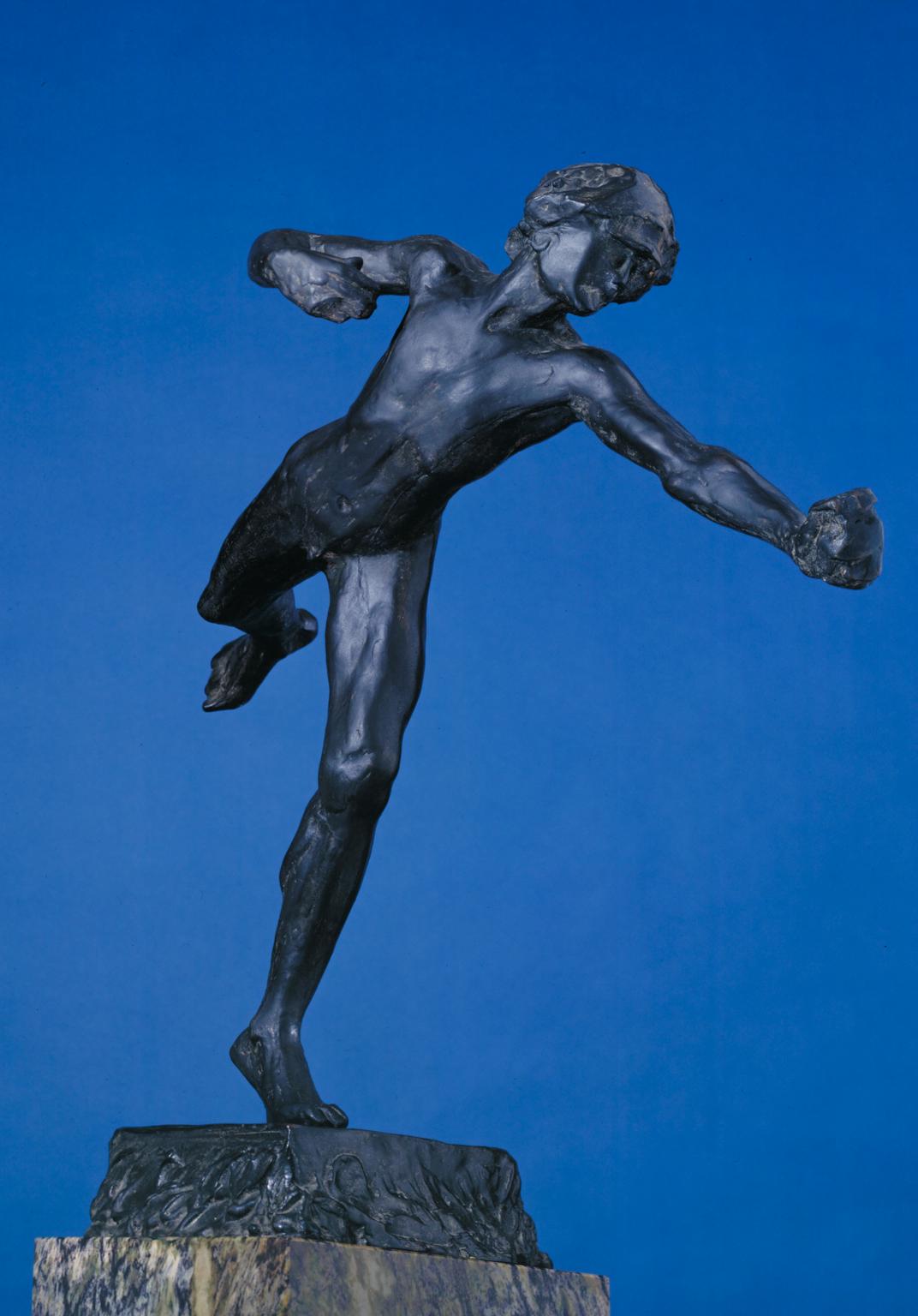

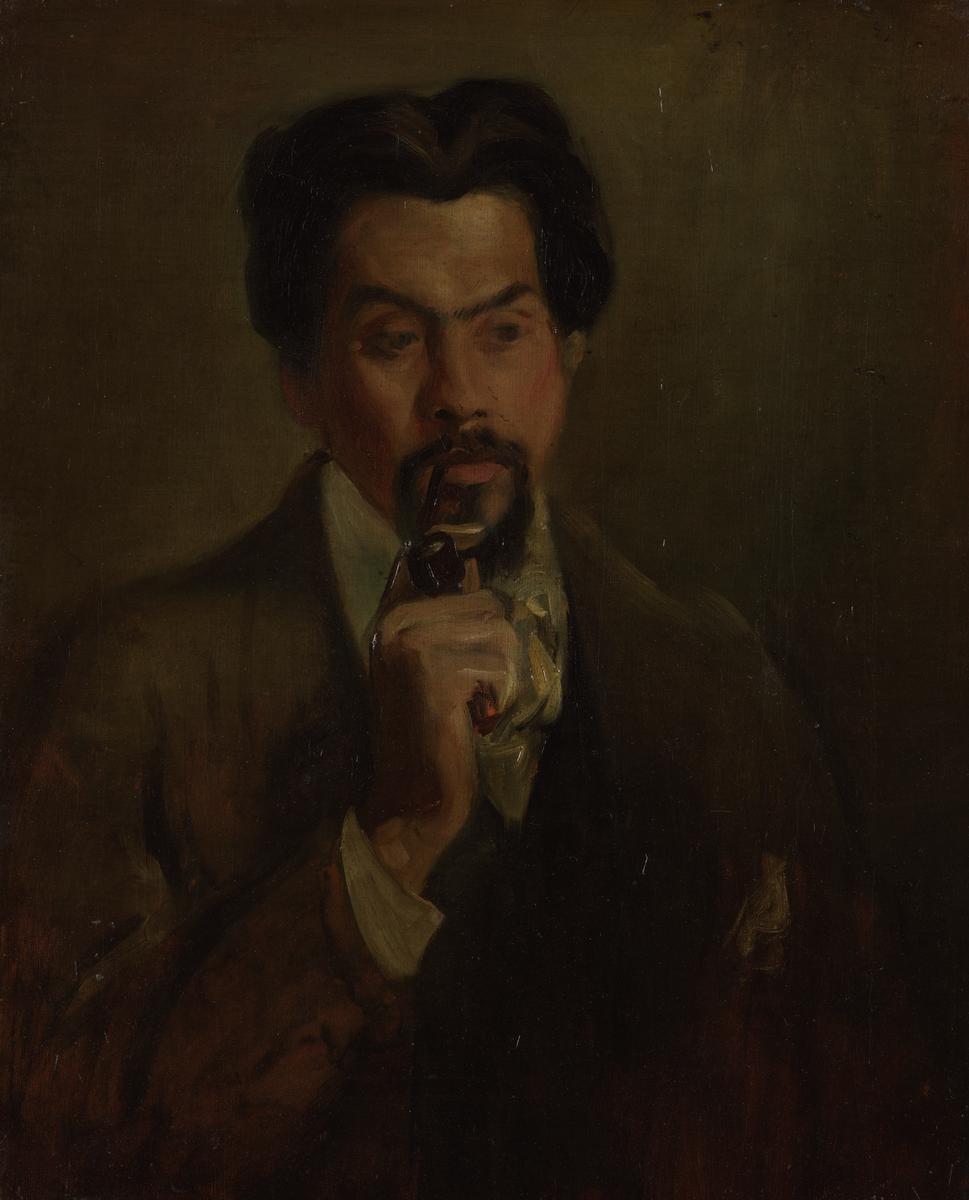

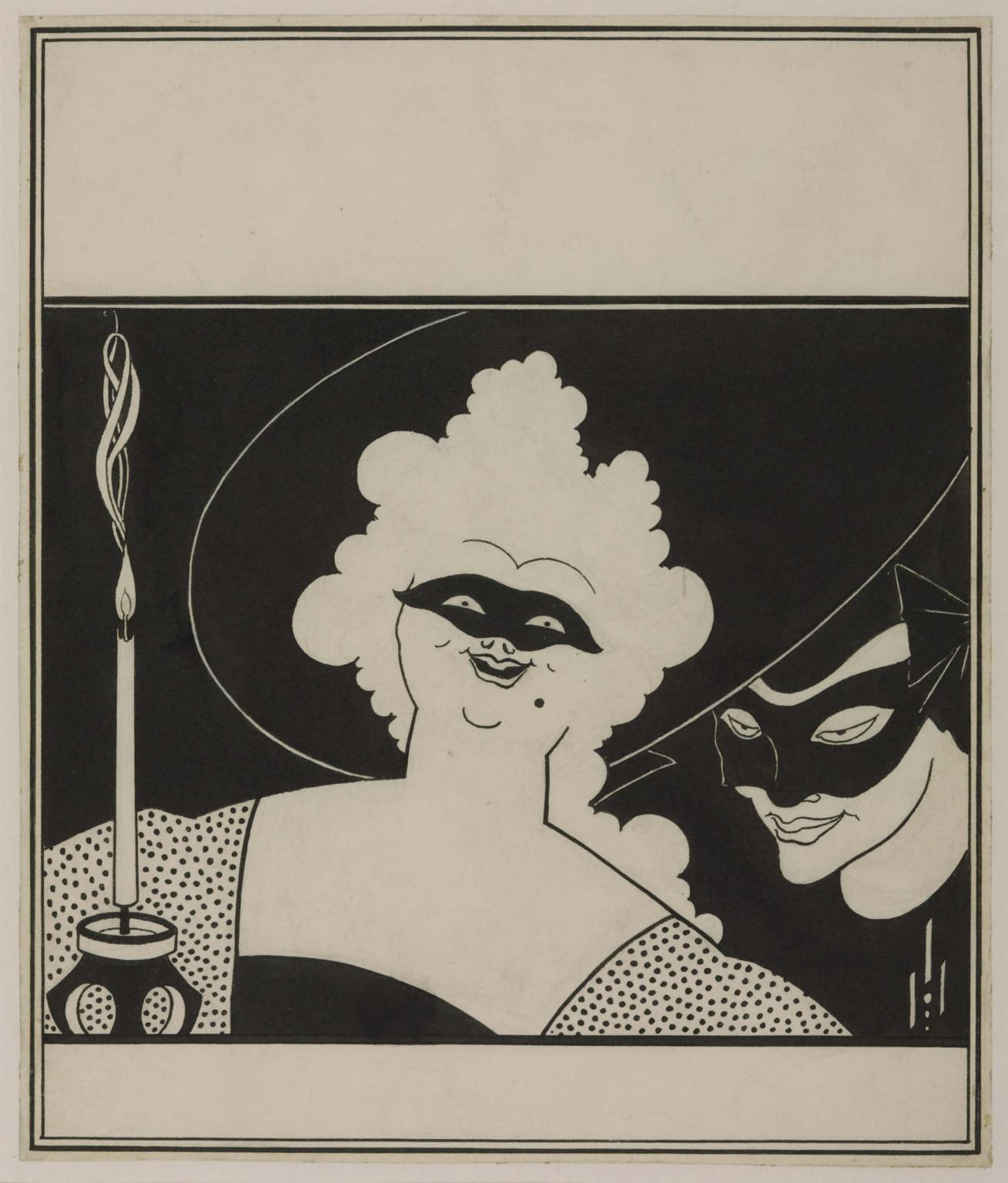

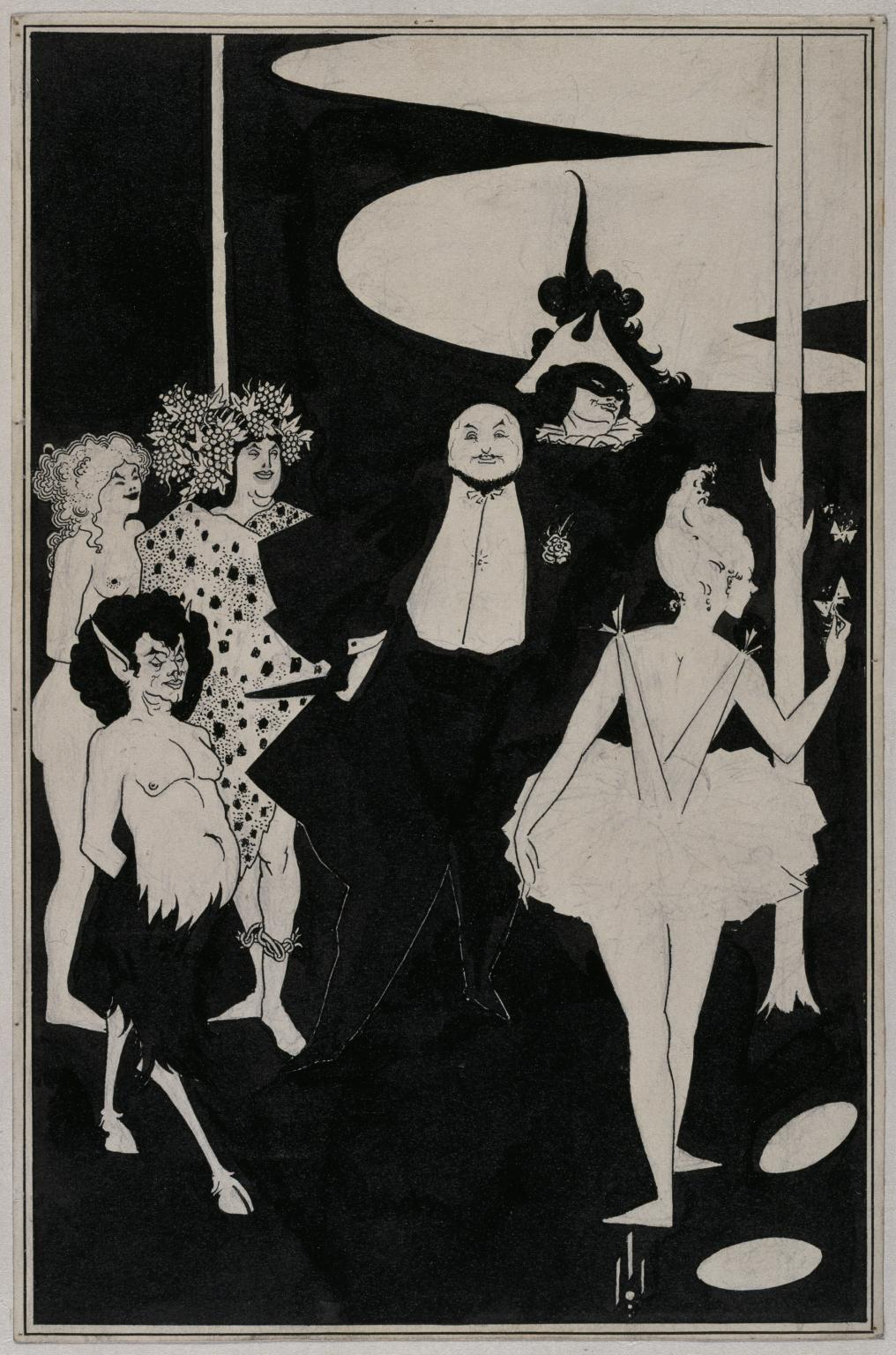

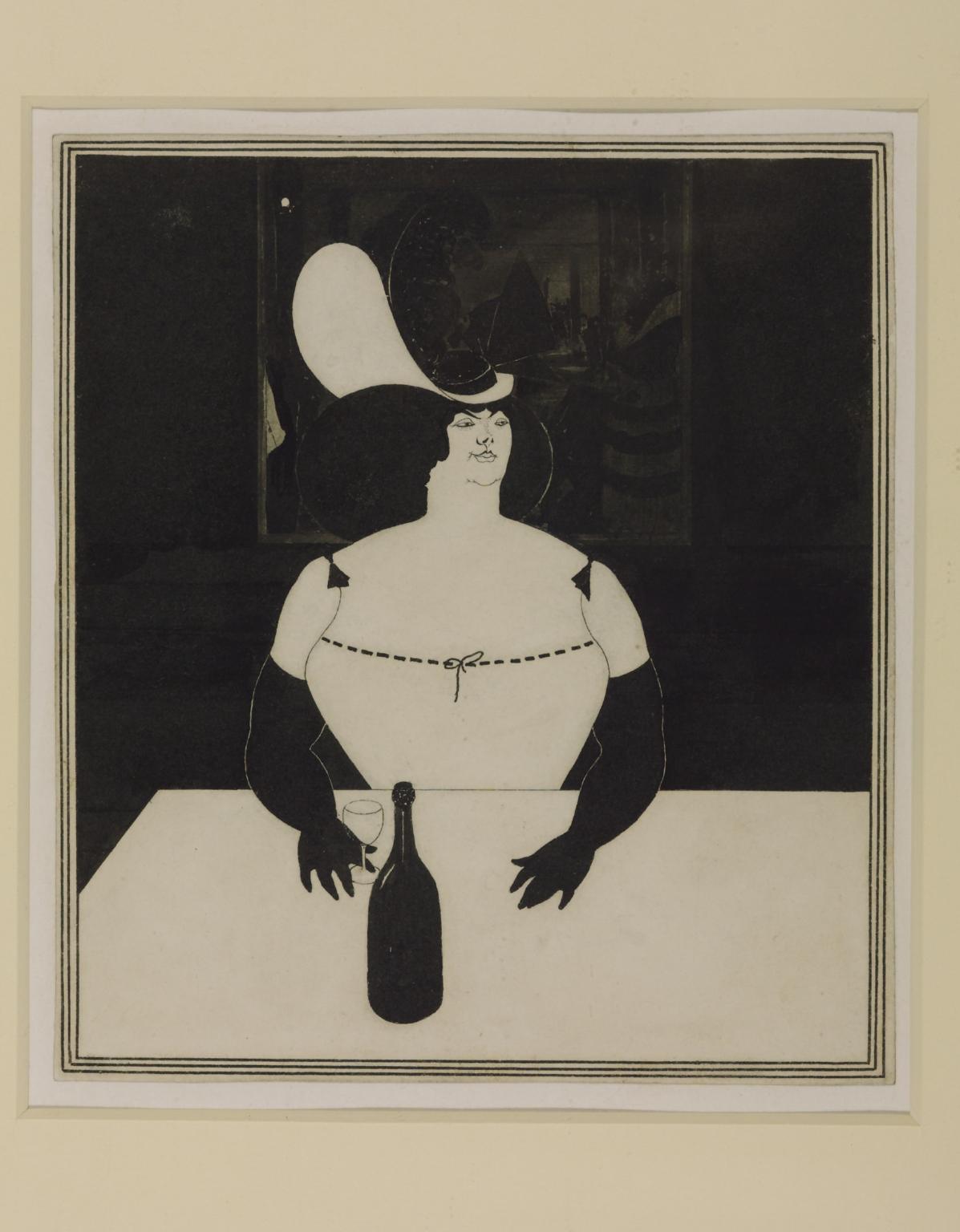

In the late 19th century, Victorian moral certainties and social hierarchies start to crumble. Artists explore more fluid notions of personal identity, creating artworks that reflect their own experiences and desires. New ideas about psychology and the ‘self’ become popular. Artists foreground ideas of pretence and performance.

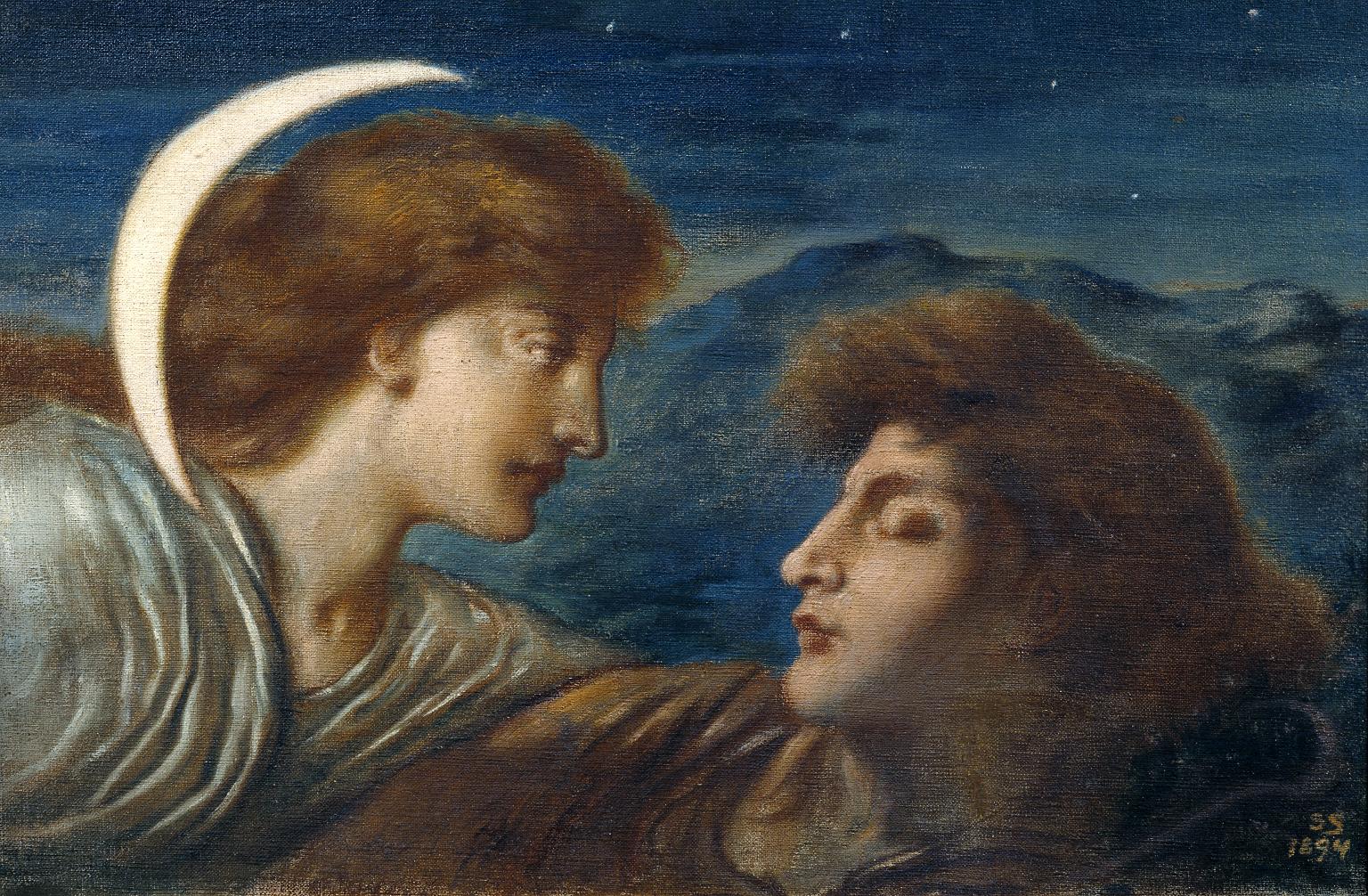

A progressive artistic culture emerges in opposition to the mainstream Victorian establishment, supported by new galleries, publications and meeting places. British artists find ways to portray subjects that were previously overlooked or actively supressed. Despite increasingly repressive legislation passed by the British parliament, queer identities become more visible through figures such as the writer Oscar Wilde. Some artists use dream-like symbolism to place concealed stories and narratives in their work, while rejecting the explicit moral values of 19th-century art. These artists argue that art should be judged by how beautiful it is, or how it engages the senses, calling this ‘art for art’s sake’.

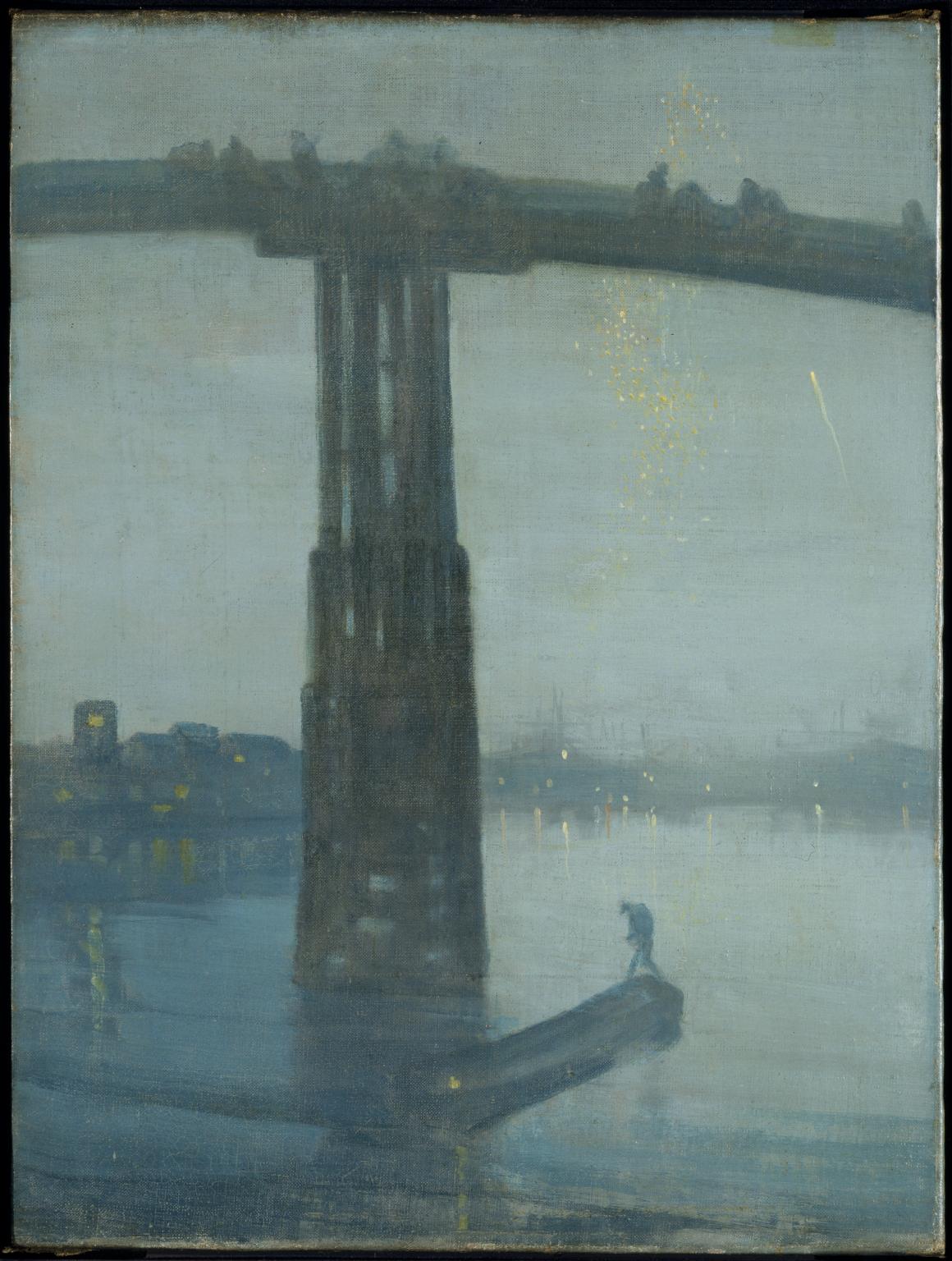

These artists rarely address commerce, industry and empire explicitly, despite the increasing ease of international travel. Instead, they borrow styles and subjects from around the world, particularly Japan, which has recently resumed trade with Europe.

Art in this room

You've viewed 6/18 artworks

You've viewed 18/18 artworks